The Plantsman’s Choice

Elm as a future urban tree: is it possible?

Dr Henrik Sjöman and Dr Andrew Hirons

The high tolerance of many elms to challenging urban conditions, combined with their ease of establishment, meant that they were widely appreciated across Europe and North America until their near-complete demise as a result of Dutch elm disease (DED). Today, as we seek long-term sustainable tree species for our towns and cities, there is a great desire to make the elm part of our urban treescape once again.

In Europe and North America, the elm (Ulmus spp.) was historically one of the most common urban trees until the end of the 20th century. Parts of Amsterdam in the Netherlands had over 70% elm along their streets and in their parks. Cities such as Malmö in Sweden were also proud of their majestic elms. It seems that in the eyes of some policy makers there was no reason to break a winning concept: all other trees were worse in comparison; it had to be elm on elm. However, these cities experienced the catastrophic effects of over-reliance on one type of plant material as the DED epidemic struck. Such widespread mortality of such a profoundly dominant tree was a bitter blow to many towns and cities. The effects of these losses can still be observed today.

Therefore, proposing elm once again as a city tree may seem unthinkable, but thanks to the hard work of tree breeders, it is now a realistic prospect. We know that many Asian species of elm are resistant to the serious type of DED, which has led them to be used in extensive hybridization work to produce DED-resistant trees. Many of these selected cultivars are of North American origin, including two that we have a substantial experience of now: the so-called Resista® elms, ‘New Horizon’ and ‘Rebona’. In order to succeed with them, however, you must know their background, so that you can more easily understand their capacity for growing in urban environments, as well as the care they may require.

Both cultivars are American hybrids from the University of Wisconsin and both have the Siberian elm (Ulmus pumila) and Japanese elm (Ulmus davidiana var. japonica) as their parents. It’s important to note that the characteristics of Siberian elm are such that its genes might be considered something of a mixed blessing.

In fact, some of what is said about the Siberian elm would not be polite to put into print. Suffice to say that some consider its weed-like growth, which results in an untamed, wild crown perched atop a stick, makes it one of the worse trees you can grow. However, the advantage of the species is its outstanding tolerance for hot and dry conditions, attributes that have served it well in its native regions around the edges of the Gobi Desert in northern China. So, having Siberian elm as a parent in these cultivars means that you get trees that are tolerant to the most challenging of urban environments and that quickly establish and grow fast. On the other hand, you also get trees with a rather messy crown structure, which is particularly difficult to manage at a young age when branching can be very dense and irregular. This means that it is wise to buy larger plant material (trunk size at least 25–30cm circumference at 1m) where the nursery has already done the difficult and extensive work of building an even and attractive crown structure.

Ulmus ‘New Horizon’.

Ulmus ‘New Horizon’.

Ulmus ‘New Horizon’

Early-mature trees of the cultivar develop with an oval crown, 10–12m high and 4m wide, but over time they can become significantly wider, usually with a continuous single trunk and a dense but fairly evenly distributed branch structure. The dimensions of the mature tree are listed by German nurseries as 25m × 10m. The cultivar enjoys heat and is a really good inner-city tree; its wind resistance also makes it a good tree for planting adjacent to highways. The autumn colour is not spectacular though. The variety has been around for 25 years in European cultivation and in the USA for another 10–15 years and is considered completely resistant to DED.

Ulmus ‘Rebona’

This cultivar is similar to ‘New Horizon’ but has a stronger tendency to develop a consistent single trunk with a more even crown density. The leaves are also slightly larger in ‘Rebona’ compared to ‘New Horizon’. Trees of the cultivar are very fast growing and initially develop a narrow pyramidal growth pattern, 10–15m high and about 4m wide, while older trees become significantly wider. Here, too, German data describe final sizes of 25m × 10m. ‘Rebona’ is also heat tolerant, wind resistant and it has proven to be resistant to flooding. The cultivar is somewhat newer and thus has not been tested as long as ‘New Horizon’, but it has shown remarkable tolerance for inner-city environments.

Ulmus ‘Rebona’.

Dr Henrik Sjöman is a Lecturer at the Swedish University of Agriculture Sciences and a Scientific Curator at Gothenburg Botanic Garden.

Dr Andrew Hirons is a Senior Lecturer in Arboriculture and Urban Forestry at University Centre Myerscough.

This article was taken form Issue 191 Winter 2020 of the ARB Magazine, which is available to view free to Arboricultural Association members by simply logging in to the website and viewing your profile area.

Could businesses help fund our urban trees?

by Helen Davies

Passionate about enhancing green infrastructure in our cities, I’ve spent the past three years undertaking a PhD at the University of Southampton looking at how to increase funding for urban trees.

There is now a wealth of research showing how the right trees in the right places can help mitigate city problems such as surface water flooding, air pollution, and the urban heat island, whilst also enhancing human wellbeing.1 However, there is little published information to suggest that urban forests in the UK are being planned and managed with these benefits in mind.

Limited council resources

In 2016, I interviewed local authority tree officers from 15 of the UK’s largest and most densely populated cities (outside of London) to find out whether provision of ecosystem services is an objective of urban forest management, and if not, what could be done to address this.2 The tree officers were as passionate about the benefits of trees as I am; however, I was dismayed to find that due to limited (and seemingly ever dwindling) financial resources almost all of them are forced to manage their urban forests reactively, in response to complaints and safety risks. Even more worryingly, there was a strong perception amongst the tree officers that other council departments, politicians, businesses and citizens do not care about trees, and are not aware of the benefits they provide.

When I asked the tree officers what would facilitate their taking an ‘ecosystems approach’ to urban forest management, three opportunities were put forward. Firstly, raising awareness of the benefits of the local tree resource through i-Tree Eco studies (or similar).3 Secondly, adopting forwardthinking tree and woodland strategies. And finally, obtaining additional funding for tree planting and maintenance from those who benefit, such as businesses and citizens. One-third of those interviewed already receive small, ad hoc contributions to their budget from sponsorship or corporate social responsibility activities, but this has so far been insufficient for sustained tree planting. As such, the majority of tree officers were keen to explore the potential for novel funding streams such as a targeted, public-private ‘payments for ecosystem services’ (PES) scheme.

Payments for ecosystem services

PES, in a nutshell, involves those who use or benefit from nature’s services giving payments to the providers (or stewards) of those services. Increasingly common in rural areas in countries worldwide, PES schemes based entirely in urban areas are rare – particularly those funded by businesses. Some researchers have suggested this is likely to be because of the complexity of urban environments, with fragmented habitats, a multitude of different landowners, and numerous stakeholders potentially hoping to free-ride on the contributions of others.

During 2012–15, the UK government funded three urban PES pilot projects to test the of PES in new contexts, two of which were successful in enticing private sector funders.4 For example, in the northern city of Hull, the local water company was willing to pay land managers to reduce flood risk through better management of green infrastructure. In the southern town of Luton, the local water company, two large businesses, and some local residents were willing to contribute to enhancing the amenity, recreation, biodiversity, water quality, and flood regulation services provided by a riparian park. However, the pilot in the city of Manchester was unsuccessful, due to inadequate incentives amongst interviewed businesses to fund improvements to the river in return for enhanced aesthetics, water quality, biodiversity, recreation, or flood or heat regulation.

Urban forest PES schemes

In terms of corporate funding of urban forestbased ecosystem services, I have not identified any schemes labelled as PES. The nearest example I came across in the UK is Tree Time,5 a social enterprise set up in 2015 offering corporate sponsorship packages to support tree planting in Edinburgh. However, there has been limited take-up by the private sector, and Tree Time is soon to be re-launched with a focus on contributions from individuals.

Three similar schemes have been set up outside of the UK in the past year or so. City Forest Credits6 is a non-profit organisation that has had success attracting private sector buyers for tree planting across the United States; whilst the PadovaO27 project in Italy has so far planted 2,500 city trees from €50,000 of business donations. However, the Urban Forest Fund8 in Melbourne, Australia, has received interest from local residents, rather than businesses. I therefore decided to focus the remainder of my research on looking into the feasibility of beneficiary-funded urban forest PES schemes, using the city of Southampton as a case study.

New urban trees funded by Investec through Tree Time Edinburgh. (Photo: Richard Darke)

Radisson staff carrying out voluntary tree maintenance work at an urban site in Bristol. (Photo: Bristol City Council)

Business attitudes to trees

In 2017, I conducted questionnaire-based interviews with 30 businesses of varying sizes and sectors to ascertain their level of interest in a possible business-funded urban forest PES scheme in Southampton.9 I was very pleasantly surprised, both by their knowledge of a range of regulating and cultural ecosystem services, and by their positive attitudes towards investing in the planting and maintenance of urban trees.

In sharp contrast to the tree officers’ perceptions that companies ‘wouldn’t care’ about ecosystem services, those in Southampton rated tree benefits as significantly more important to their businesses than tree nuisances. The business respondents considered trees to be particularly beneficial regarding aesthetic beauty, air purification, and employee health and wellbeing. Six respondents even suggested that urban trees in the vicinity of their premises bring them financial rewards, for example through higher staff productivity, fewer sick days, and attracting additional customers.

Business willingness to invest

The interviewed businesses clearly appreciate the benefits they receive from the city’s trees, but would they really invest money to prolong these benefits? 90% of respondents agreed in principle to private sector contributions to the urban forest, and 94% thought a publicprivate PES scheme would be feasible. Half of the businesses even considered it their ‘moral duty’ to invest in their local environment, and further, that societal benefits would be a strong driver of their involvement.

Some international studies, however, have suggested that intrinsic motivations alone are rarely sufficient to sustain corporate investment in social and environmental projects. I found this was also the case for the Southampton businesses. For example, the thought of mandatory contributions did not appeal to many of the interviewees; the smaller businesses were particularly concerned about the financial burden of an ‘extra tax’. This perhaps gives the impression – and this did cross my mind – that businesses will support a PES scheme in theory, but then when it comes to paying they may make their excuses and take advantage of the generosity of others.

There was in fact a very good reason for their preference towards a voluntary scheme, which again supports the findings of other studies. By far the greatest motivation for involvement in an urban forest PES scheme in Southampton was the commercial benefits it would bring to the company through enhancing their image and reputation. Meeting corporate social responsibility (CSR) objectives was the second greatest motivator. As one respondent said:

‘You can have some crowing: “I funded this!” If you do it and it’s voluntary there’s a CSR benefit which is [useful for] marketing.’

While this may appear self-centred, these are businesses we’re talking about, not charities. They exist to make money, and expect returns (though not always financial) on their investments. So a winwin scenario is no bad thing, and if this is what it takes to increase funding for our urban forests, then it gets my vote.

Of course, not every business will be as aware of the benefits of trees as those who took part in my study. To facilitate large-scale business funding of urban forest-based ecosystem services, clear communication of the likely environmental, social and economic benefits will be required, drawing on both scientific evidence and the experience of similar initiatives worldwide.

New urban trees in Bristol sponsored by New World Payphones. (Photo: Bristol City Council)

Xylem staff carrying out voluntary conservation work in an urban site in Basingstoke. (Photo: Basingstoke & Deane Borough Council)

PES scheme preferences

According to the scientific literature, there are important aspects to consider when designing a PES scheme if it is to be successful. These are discussed below in the context of my Southampton study.

Firstly, which ecosystem services are being targeted, and (how) will they be measured? The businesses I interviewed in Southampton were most interested in funding tree planting and maintenance aimed at enhancing air quality. Paying to reduce flood risk and to improve aesthetics, employee wellbeing, and wildlife habitat were also of interest to at least two-thirds of those interviewed. However, the majority of businesses showed no interest in the monitoring of ecosystem service delivery to prove that they would be getting what they paid for, with some suggesting that this would add unnecessary costs to the scheme. Most businesses would be content with receiving information on the number of trees that are planted – and importantly, that survive.

Secondly, what form will the payments take, and at what spatial scale will the scheme operate? If businesses would be entering the scheme voluntarily, then those in Southampton would prefer to choose from a list of location specific projects to fund directly, as this would help with CSR reporting, marketing, and engagement of staff. I suggested that the PES scheme would operate city-wide, but only 40% of respondents would be interested in contributing to the city’s trees as a whole; 60% would prefer to invest only in trees in the immediate vicinity of their business premises in order to ensure direct as well as indirect benefits (though of course this isn’t necessarily the best way to utilise trees in ecosystem service delivery). If business involvement in the scheme was mandatory instead, respondents were evenly split between preferring payments to be based on company size vs. based on companies’ environmental impacts. In contrast, having a blanket rate equally payable by all businesses was not popular.

Thirdly, who holds the decision-making power over where and how the money is spent, and will inequalities in access to and use of trees and their benefits be reduced or exacerbated? One-third of the Southampton businesses wanted strong involvement in urban forest governance, ideally becoming part of a steering group, and even getting involved in the planting and maintenance work. However, the majority of respondents would be happy with minimal involvement, for example receiving annual updates regarding the tree planting projects they had helped to fund. Just over a quarter of respondents commented that trees should be planted in areas of need and/or where they are best suited, to avoid benefitting only the wealthy business districts.

Finally, will intermediaries (such as charities or NGOs) be involved? Intermediaries are common in PES schemes and have been found to improve coordination and trust between beneficiaries and ecosystem service providers. They can help to cover the costs of upfront canvassing, administration and transaction costs that are needed to get PES schemes off the ground. There was no requirement for an intermediary amongst the Southampton businesses, as they were willing to pay the council directly, but it is difficult to imagine an urban forest PES scheme getting underway without one. For example, though Southampton City Council was sufficiently interested in the results of this study to call a meeting with me, due to capacity and financial issues they would unfortunately only be able to support an urban forest PES scheme if another party took the lead. It would be useful now to have a conversation with some tree/woodland and environmental charities.

New urban trees in Cardiff sponsored by Cardiff Holiday Homes (Photo: Cardiff City Council)

Citizen funding of urban forests

Around two-thirds of the tree officers and businesses I interviewed each thought that citizens should also contribute to the benefits they receive from the urban forest, whether this be through a tax, community-based grants, sponsorship, or voluntary work. Consequently, in 2018, I ran an online survey (comprising what is known as a ‘choice experiment’) with 362 of Southampton’s residents to determine their willingness-to-pay for urban forest-based ecosystem services.10 The vast majority of respondents (93%) were willing to contribute financially to my proposed, city-wide street tree planting programme. Though I won’t discuss the results in detail here, the average amount that respondents were willing to pay for the tax-based programme (including basic air purification, flood risk reduction, and aesthetic benefits) was £140 per household per year. I also discovered that uncertainty surrounding the likelihood of air quality and flood reduction benefits being delivered by trees reduced people’s willingness-to-pay. However, telling people about these uncertainties had less of an effect on their willingness-to-pay than did their own personal doubts about ecosystem services delivery.

Conclusions

The core finding of my research is that a public-private partnership between local authorities, businesses and citizens holds strong potential for improving both appreciation of and financial support for urban forests. The tree officers were keen to explore a beneficiary-pays approach, whilst both businesses and citizens were strongly supportive of contributing financially to tree planting and maintenance in Southampton, particularly for air purification benefits. I hope that my research will be of use to you as arboricultural professionals, and that it may help facilitate a move towards an ecosystems approach to urban forest planning, governance, management, and funding.

With thanks to my PhD funding bodies (the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council, the University of Southampton, the Scottish Forestry Trust, and Forest Research) and the tree officers, businesses and citizens who participated in my studies.

Helen Davies

CEnv MIEMA ACIEEM is Principal Environmental Consultant at WSP, one of the world’s leading engineering firms.

She is responsible for integrating ecosystem services into environmental assessments of government plans and development projects. In her spare time, as well as finishing off her PhD(!), Helen volunteers as the Tree Warden for Basingstoke & Deane Borough Council.

Footnotes:

1 H. Davies, K. Doick, P. Handley, L. O’Brien and J. Wilson (2017), ‘Delivery of Ecosystem Services by Urban Forests’: www.forestry.gov.uk/PDF/FCRP026.pdf/$FILE/FCRP026.pdf

2 H.J. Davies, K.J. Doick, M.D. Hudson and K. Schreckenberg (2017), ‘Challenges for tree officers to enhance the provision of regulating ecosystem services from urban forests’: doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2017.03.020

3 i-Tree tools: www.itreetools.org/ and www.forestresearch.gov.uk/research/i-tree-eco/

4 Defra (2016), Payments for Ecosystem Services: Review of pilot projects, 2012–15: www.gov.uk/government/publications/payments-for-ecosystemservices-review-of-pilot-projects-2011-to-2013

5 Tree Time Edinburgh: www.tree-time.com/

6 City Forest Credits: www.cityforestcredits.org/

7 PadovaO2: www.wownature.eu/host/padova-o2/

8 Melbourne’s Urban Forest Fund: www.melbourne.vic.gov.au/community/greening-the-city/urban-forest-fund/Pages/urban-forest-fund.aspx

9 H.J. Davies, K.J. Doick, M.D. Hudson, M. Schaafsma, K. Schreckenberg and G. Valatin (2018), ‘Business attitudes towards funding ecosystem services provided by urban forests’: doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoser.2018.07.006

10 ‘Citizen attitudes towards a new tree planting programme in Southampton’: www.soton-tree.uk/

This article was taken form Issue 185 Summer 2019 of the ARB Magazine.

Watering young trees in dry weather

Newly-planted trees need to be watered regularly over the summer months if they are going to become established and thrive.

If you have a tree outside your house, or one that you pass on your daily walk, then you can help.

Requirements vary depending on a number of factors such as species and location, but a general rule is that they should receive at least 50 litres of water per week in May, June, July and August:

Please water regularly during dry periods with as much as you can – Every little helps

More information about tree watering can be found in the London Tree Officers Association (LTOA) publication Sustainable water management, available for free download at www.ltoa.org.uk

General information about trees and tree care can be found at the Arboricultural Association website www.trees.org.uk

Fersiwn Gymraeg (Welsh Version)

Campaign Translations

Polish

Spanish

Please Note:

If you would like to add your Local Authority or Community Group logo to the tree watering tags then please feel free to do so; however please ensure that this does not replace the logos of the Arboricultural Association, London Tree Officers Association Municipal Tree Officers Association and Association of Tree Officers – the original logos must remain on the tags.

Tree Selection, Planting and Maintenance

Selecting the right tree for the right place

Planting a tree in your garden is a decision requiring forethought and planning. Consideration must be given to the surrounding landscape and buildings, space available, soil type and location of the particular site.

Careful thought will help to ensure that an appropriate species is selected for the particular location, so giving the tree the best chance of successful establishment and future growth.

The Trees and Design Action Group (TDAG) offer comprehensive guidance with their resource Tree Species Selection for Green Infrastructure: A Guide for Specifiers, which includes information for over 280 species on their use-potential, size and crown characteristics, natural habitat, environmental tolerance, ornamental qualities, potential issues to be aware of, and notable varieties.

Further advice and information can be obtained from the Help & Advice section of this website as well as an AA Registered Consultant.

Tree planting

It is essential that young trees are given every opportunity to survive planting. Poor planting practices can result in long-term problems and even the death of the tree.

Information on how to plant your trees can be obtained from a competent Arboricultural Consultant, a competent Arboricultural Contractor, Specialist tree planting contractors or Tree nurseries.

Maintenance in the first few years following planting is crucial to ensure establishment. Young trees need TLC:

- Tending – check stakes, ties, guards and prune out broken and diseased branches

- Loosen ties and remove the stake altogether if the tree is stable

- Clear vegetation from around the base

- Add water when required

Tree maintenance

Most trees do not require regular pruning but there are occasions when tree work is necessary. You must take great care in deciding who you will take advice from.

Trees can suffer ill health from pests and diseases and or as a result of climatic or environmental changes.

If your tree looks unwell, appears different to normal or you consider that tree works might be required, you can obtain guidance and advice from the following sources:

- A competent Arboricultural Consultant

- A competent Arboricultural Contractor

- Download this leaflet – ‘Tree Work: Choosing your tree surgeon (arborist)’

- Download this leaflet – ‘Guide to Tree Pruning’

- Visit our Help & Advice section of this website

New guide to use of cellular confinement systems near trees

The Association’s Guidance Note 12: The Use of Cellular Confinement Systems near Trees is now available to download here.

Tree roots can be damaged by soil stripping, and the volume of viable soil available to a tree can be reduced if soil is compacted or sealed from above. For these reasons, the introduction of new hard surfacing within root protection areas should only be specified when other alternatives are not feasible. However, with increasing pressure to open up land for development it is now common for the installation of driveways, car parks, cycle paths and footpaths to be required within tree root protection areas.

In such cases, where the adjacent trees are to be retained, the soil needs to be protected in some way. When no-dig surfacing is required near trees, a cellular confinement system sub-base is currently the most used approach, but there are alternative construction techniques which may sometimes provide a better solution, such as piled rafts using conventional or screw piles, or the use of stone-filled wire gabions.

Above-ground cellular confinement systems have been employed to install surfacing near trees in the UK for over 20 years, but their use is not always a simple matter and the limitations of the approach are often misunderstood. Until now the only guidance on this subject available for arboricultural professionals was Arboricultural Practice Note 12, which was a short guide published in 2007. The new good practice guide – Arboricultural Association Guidance Note 12 – describes in more detail how cellular confinement systems can be used for ground protection near trees and draws on industry experience to provide practical advice on how to specify and install new hard surfacing above tree root zones.

It aims to inform specifiers and contractors by discussing the environmental factors that need to be considered and by explaining the engineering principles that effective cellular confinement system designs employ. However, attempts have been made to avoid the content being overly prescriptive because each site will present unique circumstances that vary with the trees present, the local soil conditions, the scale of the construction project, and the intended use.

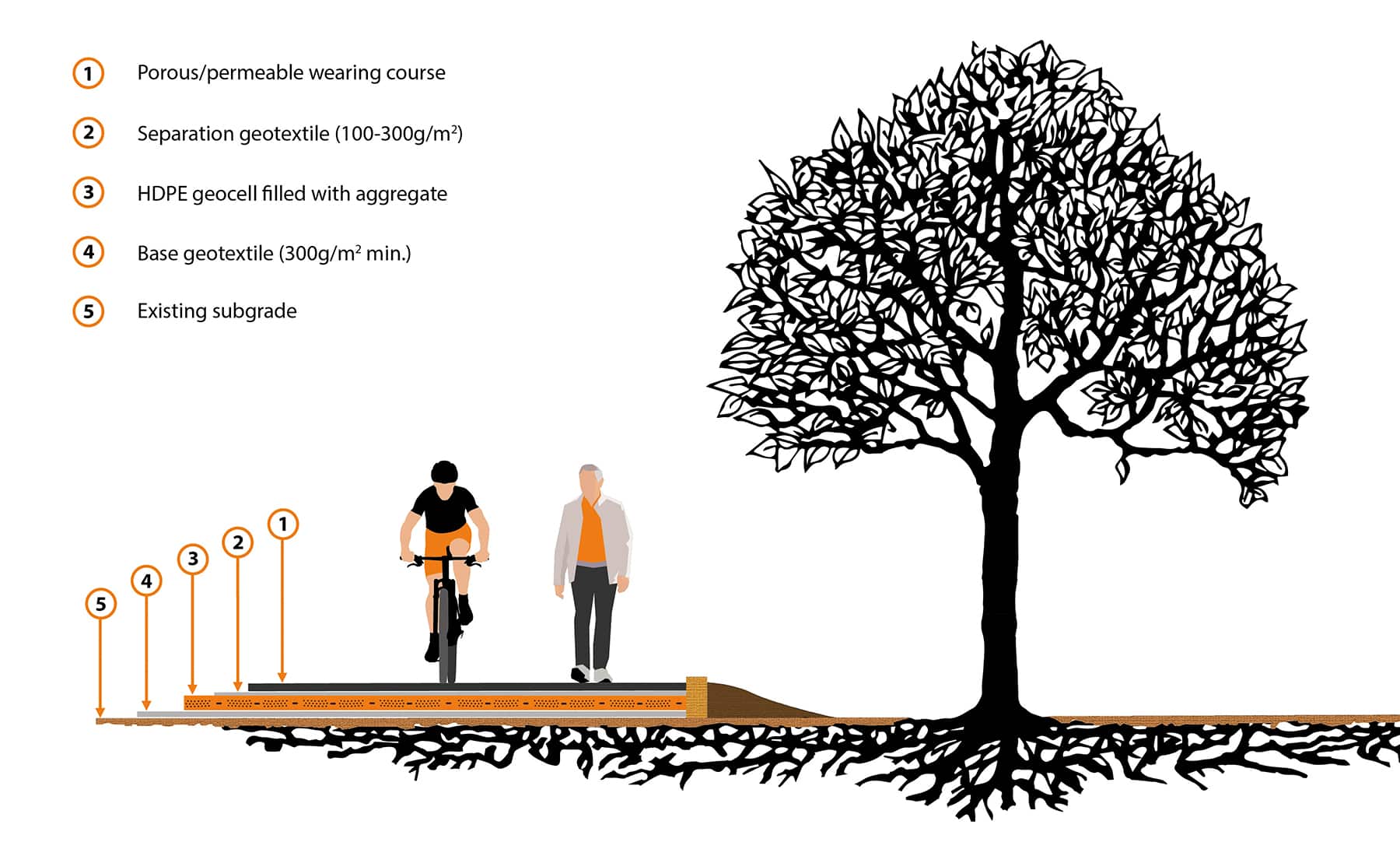

The document stipulates that high-density polyethylene (HDPE) geocells should be used when installing surfacing near trees rather than geocells made of flexible geotextiles. Suitable infill materials are described and there is guidance on the appropriate equipment to use and methods for installation. Another key recommendation is that the final top dressing of a cellular confinement system needs to be permeable.

The document makes it clear that every installation will need to be directed by a project-specific arboricultural method statement, and it strongly recommends that ground preparation works are carried out under arboricultural supervision.

The project has taken three years to complete and included wide-ranging consultation with manufacturers and arboricultural professionals. It is pertinent that the Arboricultural Association is publishing this guidance document now at a time when there is a push for towns and cities to expand their cycle path networks. It is also hoped that this guide will prove to be a useful tool to help arboriculturists detail tree protection measures for years to come.

Figure 1 from the new Guidance Note 12: The basic approach to using cellular confinement systems for ground protection near trees. (image courtesy of Core LP)