Project awarded Arboricultural Association Research Grant funding

Climber Jake Radford preparing to carry out veteranisation treatments: 70% isopropanol and 10% bleach was used to sterilise bars, chains and side-cover interiors between treatments.

Since my early days as an arb student at Cannington College in 2012 I have been fascinated by ancient and veteran trees. As many readers know, ancient trees support a diverse plethora of organisms leading to complex interacting communities of both macro- and microorganisms, with complex coevolutionary relationships.

An in-progress fungal DNA isolation from environmental samples, preparing molecular samples for amplification and sequencing.

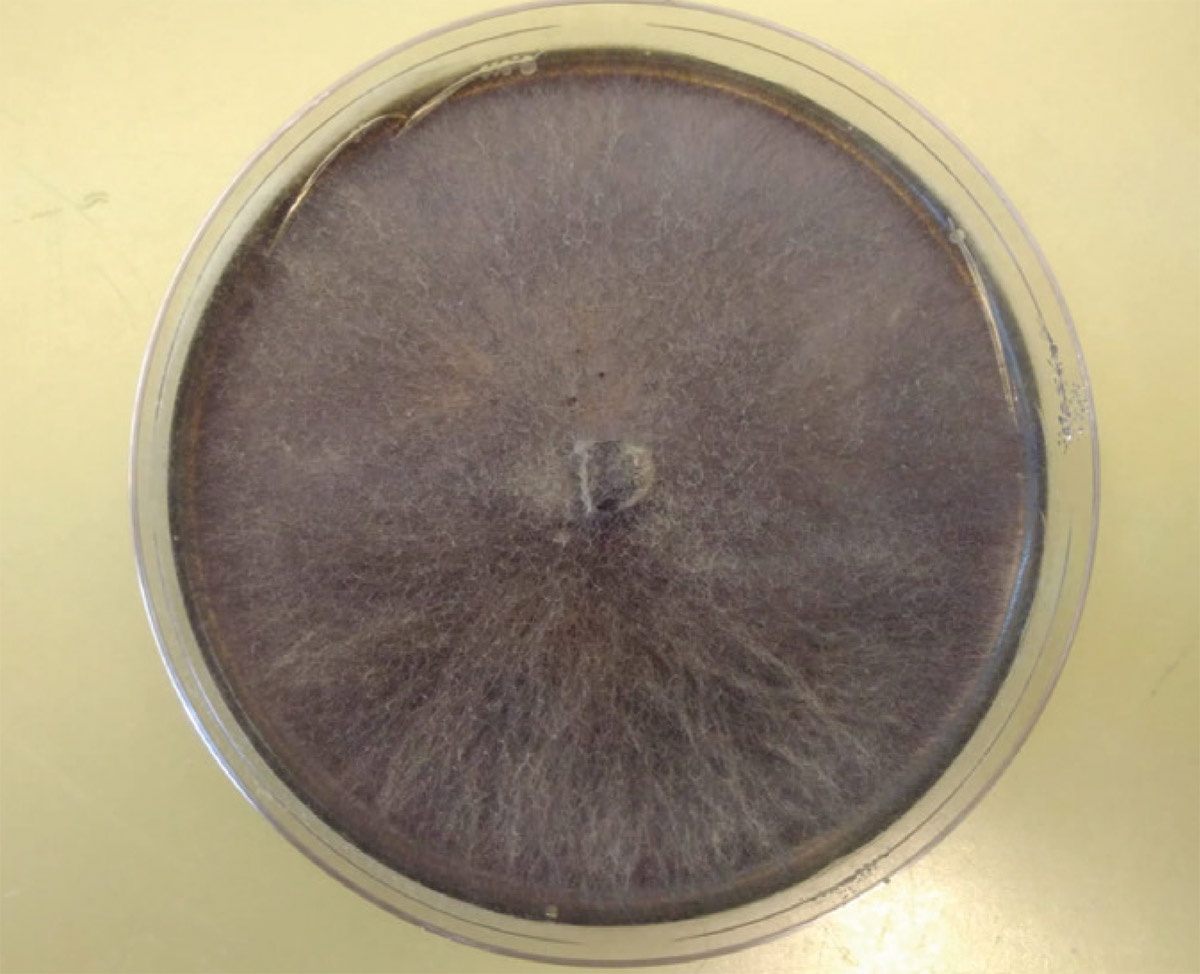

Fungal isolate grown on artificial growth medium isolated from oak canopy deadwood.

One of the distinguishing habitat features of ancient trees is a varied abundance of deadwood with varying microclimatic conditions that can be utilised by species in a myriad of ways.

Species dependent on deadwood for part – or all – of their lifecycle are termed saproxylic and are amongst the most threatened group of organisms. With a recent IUCN report claiming 18% of Europe’s saproxylic beetles are at risk of extinction due to a decline in ancient tree habitat, it is clear that action must be taken to conserve saproxylic biodiversity.

As a keen conservationist and aspiring arb, when I first learned about veteranisation practices I soon found myself with more questions than answers. How can we justify damaging healthy trees? Are the outcomes what we intended? The potential benefits of veteranisation were obvious to me, but I remained sceptical about how such sensitive work should be approached. Fast forward a few years and I am now a biology undergraduate student at Cardiff University and thanks to the AA I have a research grant to start answering these questions.

Saprotrophic fungi are the major agents of wood decomposition and one of the largest groups of organisms dependent on deadwood. Saprotrophic fungi act as ecosystem engineers, defining microhabitat characteristics as well as mediating nutrient availability to other organisms.

Setting out to investigate the impacts of veteranisation on fungal community structure, five different chainsaw treatments were designed and applied to the branches of mature oak trees. As fungal community succession is sensitive to initial colonising conditions (gaseous and moisture regimes) and the identity of initial colonisers (priority effect), it is thought that different treatments may lead to the development of distinct fungal communities.

Veteranised branches, healthy branches and branches that have died naturally will be analysed in the laboratory. First, fungi will be grown on artificial growth media in order to analyse the spatial distribution of the dominant basidiomycete community. Secondly, molecular methods will be employed to gain a deeper insight into the composition of fungal communities by extracting and sequencing fungal DNA from within the branches.

The AA research grant will help fund High-throughput DNA sequencing work for this study. Molecular methods, such as High-throughput sequencing, are a powerful tool in the identification of fungal species. Many fungal species are not readily culturable with current methods; DNA sequencing will provide further insights into community responses that are unattainable with culture-based approaches.

As arbs we are often on the front line of saproxylic conservation and have the collective ability to make a positive impact on saproxylic biodiversity. However, it is important that our management aims are supported by a strong evidence base and theoretical framework. With support from the AA I hope my research will be of use to both the practitioner and consultant. I look forward to updating the community on the progress of my research and would like to thank the AA for supporting this project.