Advice, ideas and signposting for the public

An Introductory Guide to Young Tree Establishment’ provides advice and ideas for a non-professional audience, as well as signposting readers towards other useful resources. It is not intended as a comprehensive guide, nor a replacement for specialist advice but is an important tool in sharing knowledge with the general public about arboriculture and tree care; communicating some of the key messages of the Association and hopefully helping people learn more about tree planting and aftercare.

Tree planting has never been more popular but planting a tree is just the start of the story. Arboriculturists work in tree time, not human lifespans or political cycles. If you consider the first 100 years of a tree’s life, then the act of planting might make up half an hour or so, or 0.000058%. It is undoubtedly a very important part of the process – a critical one – but there is so much more to the story…

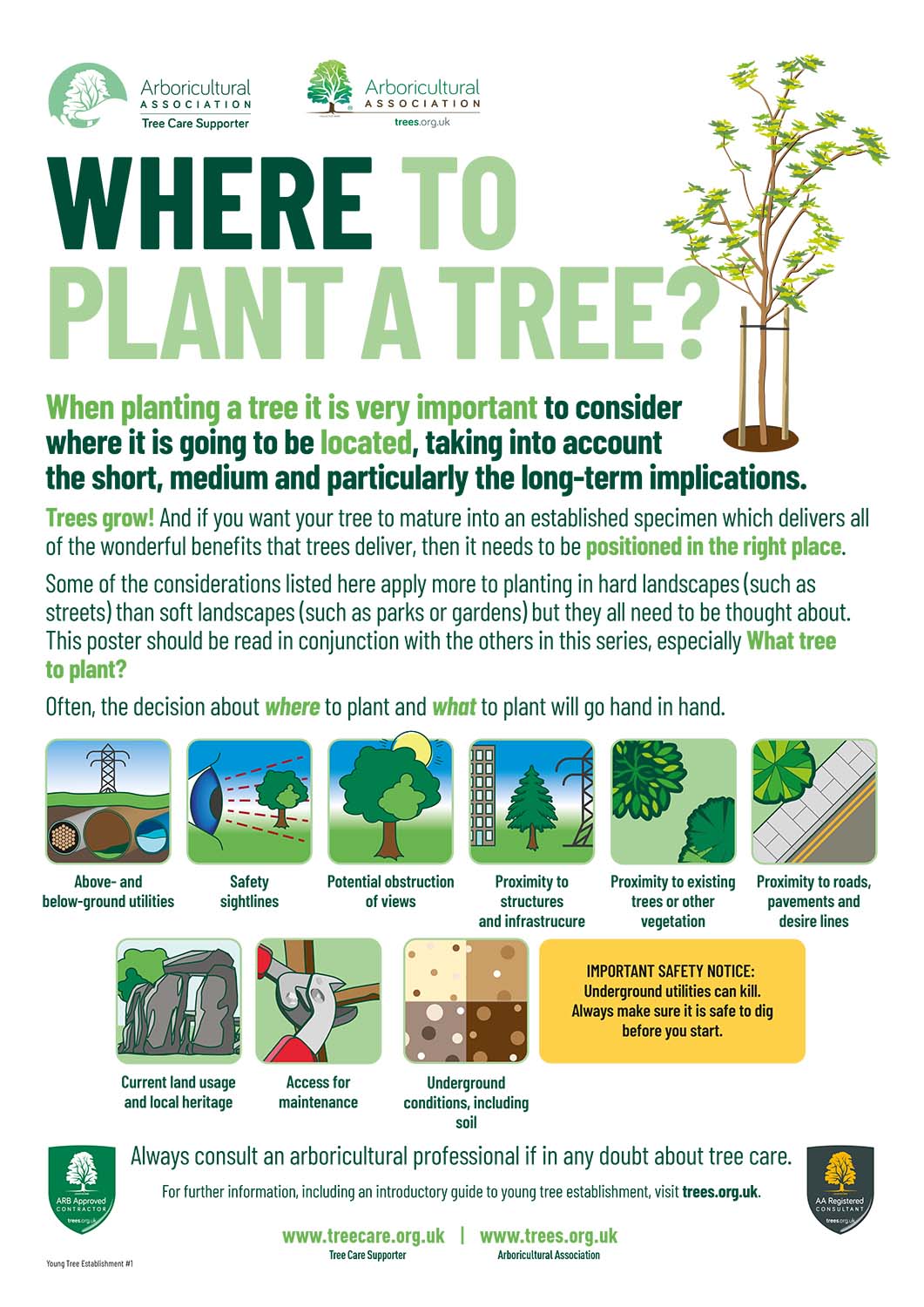

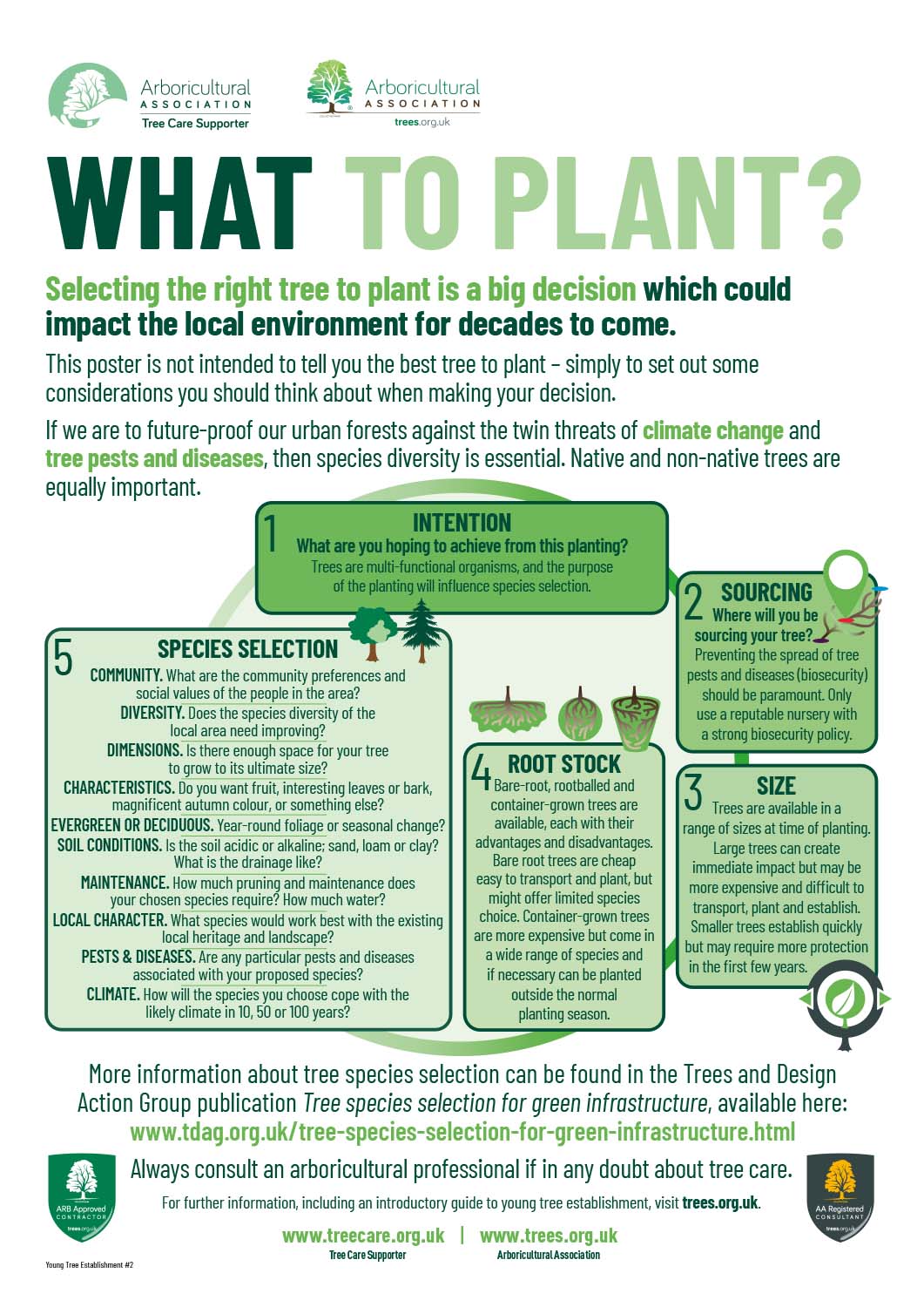

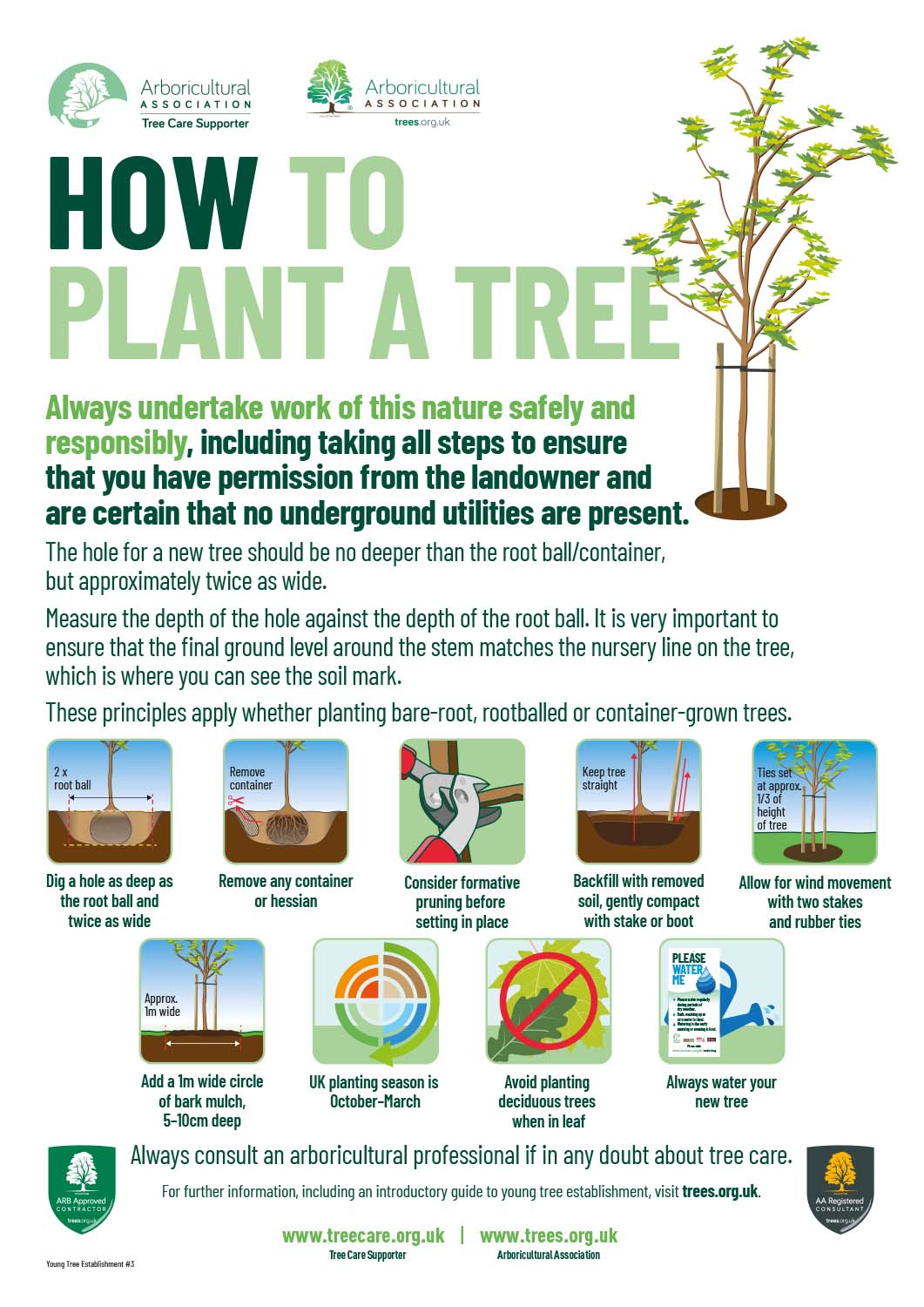

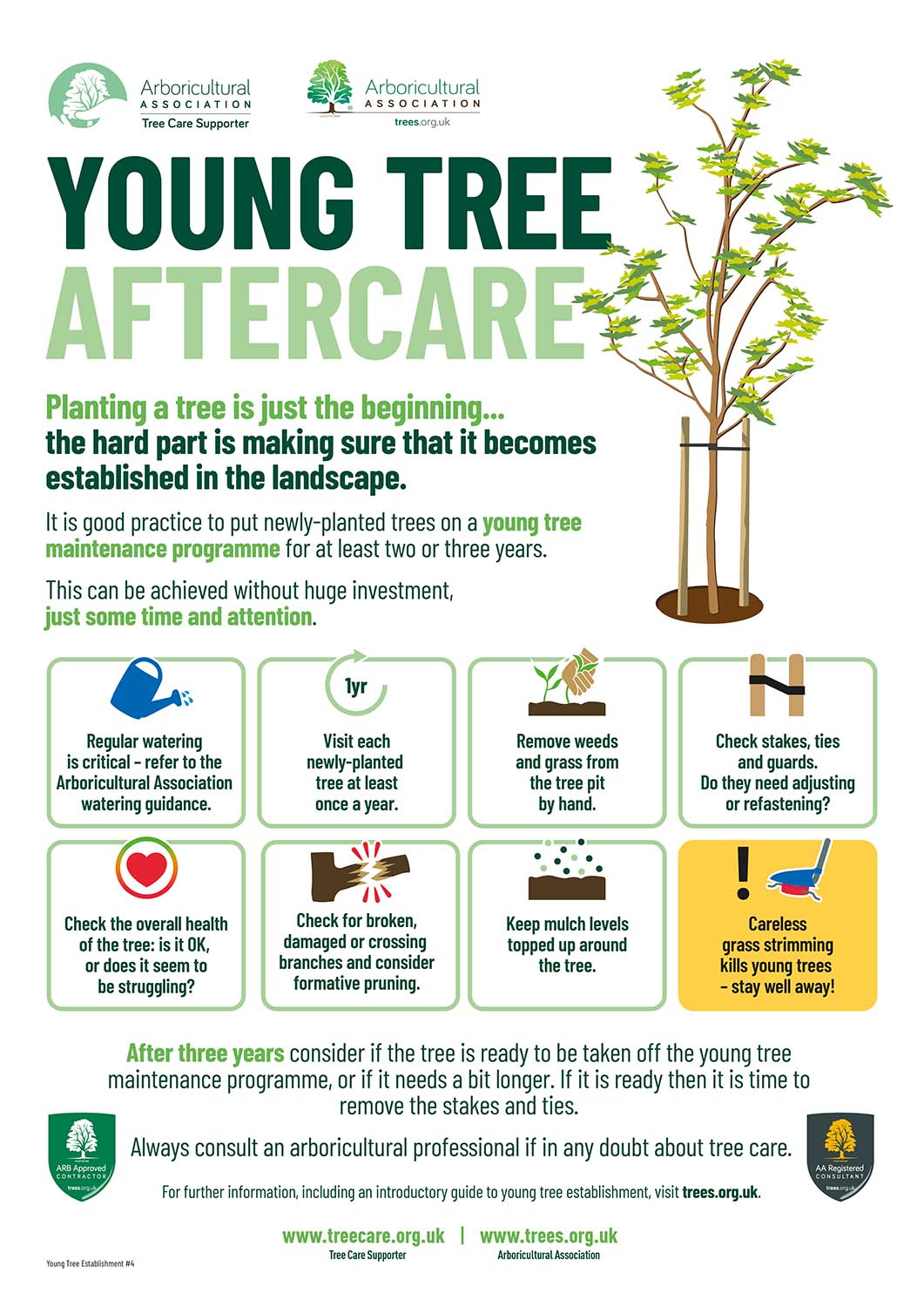

The guide is available as a free download covering key areas including ‘Why plant a tree?’, ‘Where to plant a tree?’, ‘What tree to plant?’, ‘How to plant a tree’, ‘Young tree aftercare’ and ‘Tree watering’. Free downloadable posters for each section are also available.

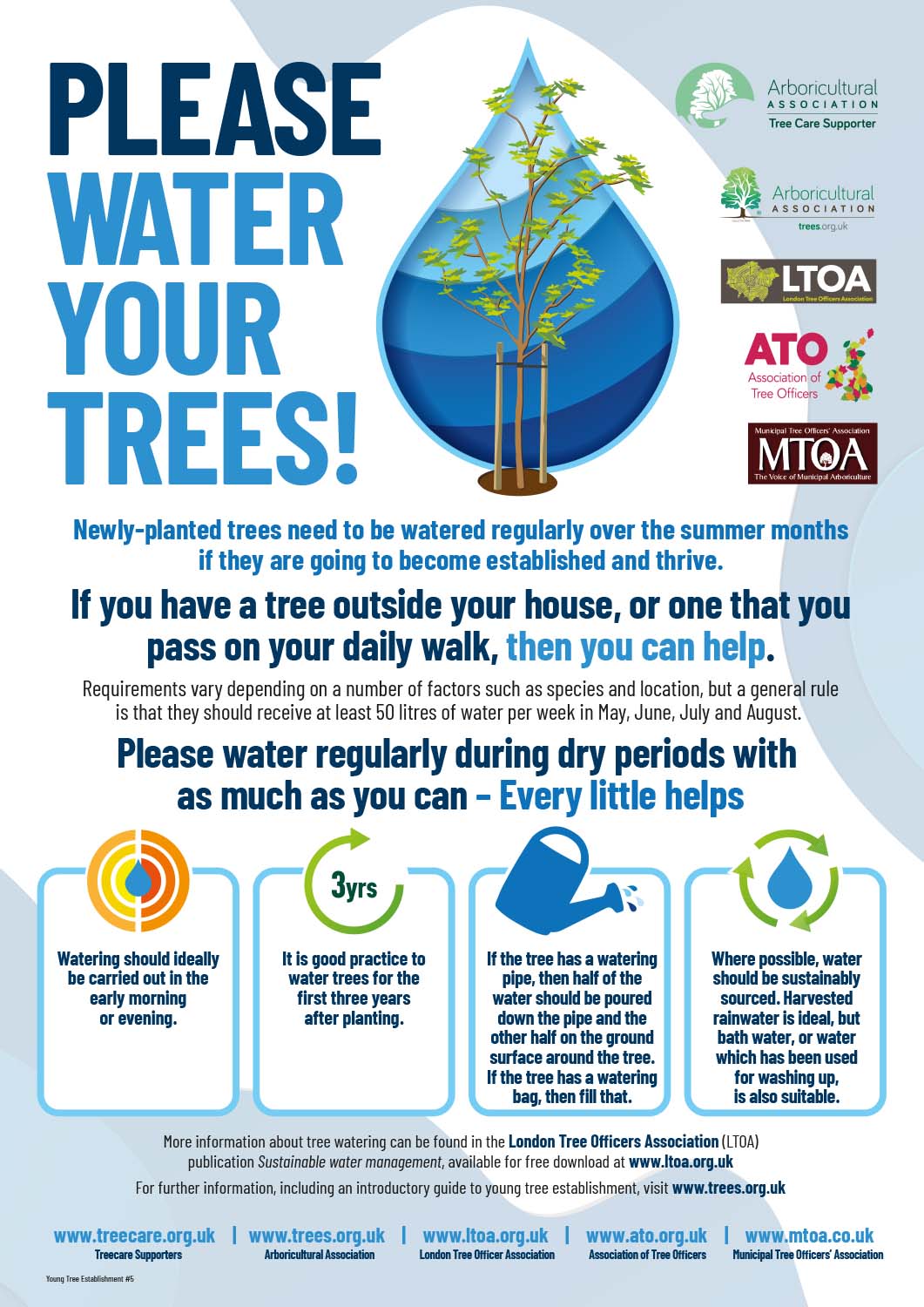

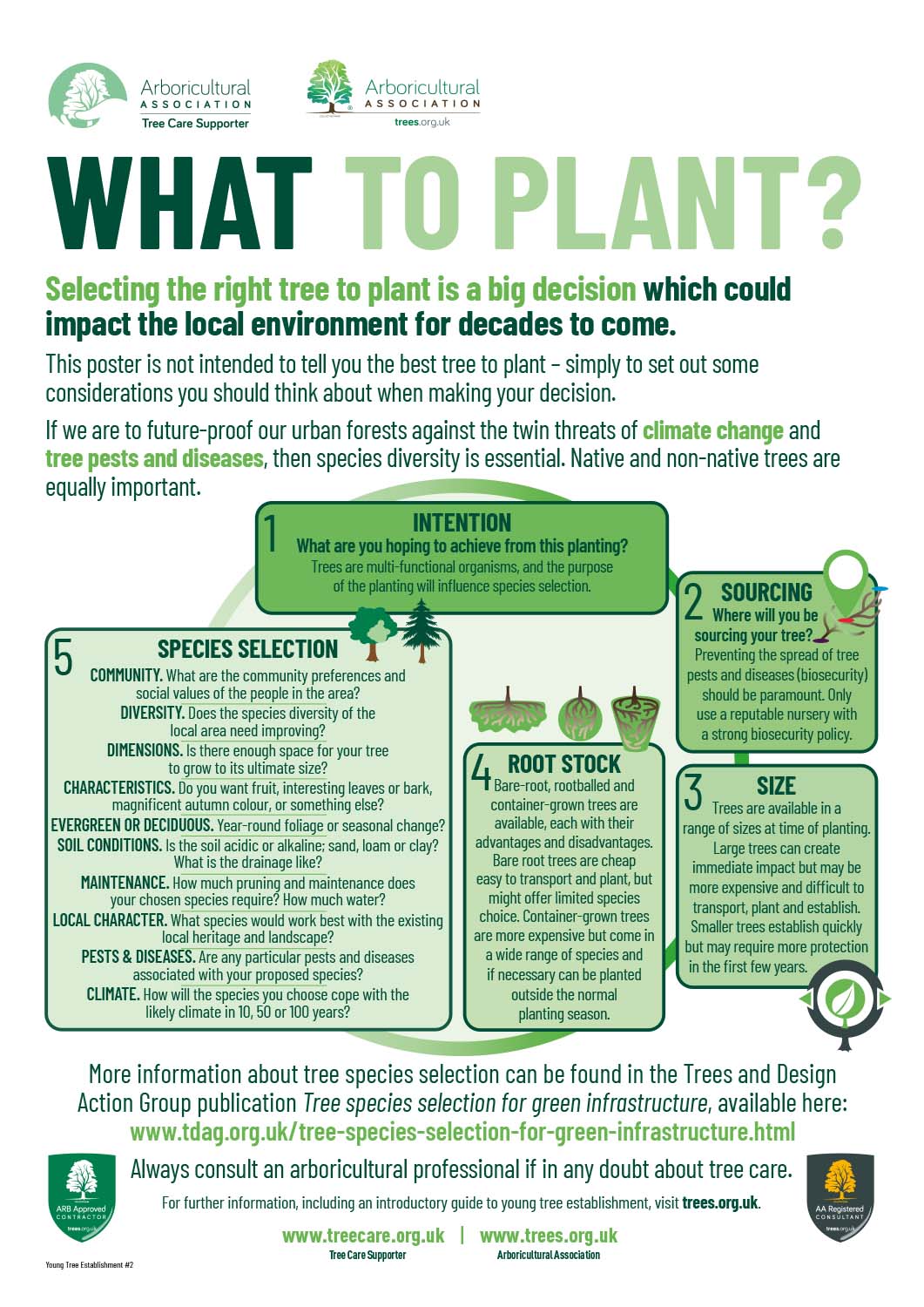

In addition to the popular guides to tree watering and young tree aftercare launched over the past 18 months, the AA has produced two more posters aimed at educating the general public on tree care best practice.

The latest additions to the Young Tree Establishment suite of documents are ‘What to plant?’ and ‘Where to plant a tree’. They have been released as a pair, with the decision about what and where to plant often going hand in hand. The former sets out some considerations to take into account when deciding on species selection, while the latter focuses on the short, medium and particularly the long-term implications.

Following the successful introduction of the AA’s tree watering campaign in 2020, which has since been translated into several languages, the ‘Guide to Young Tree Aftercare’ was launched during National Tree Week in 2021, providing an easy-to-follow young tree maintenance programme for at least two or three years.

The downloadable guidance forms part of the Arboricultural Association’s Guide to Tree Establishment series.

You can view all four guides in full below and download the PDFs.

Young Tree Aftercare - Bark damage

A guide to some of the key things to remember after tree planting with John Parker, Technical Director of the Arboricultural Association.

Young Tree Aftercare - Mulching

John Parker talks us through some of the key points to focus on in the months and years after urban trees have been planted, in this example in a community park in Stonehouse, Gloucestershire as part of the Stonehouse in Bloom community project.

Young Tree Maintenance

Video Guide

Arboricultural Association Technical Director John Parker runs over some important basic young tree maintenance.

Development near trees

Construction close to trees

Trees are easily damaged by construction works, regardless of their scale. Digging a garden pond may cause damage to trees in the same way as building demolition and construction.

It is important to ensure that trees are adequately assessed before ANY work takes place.

This is a complex topic. The specialists who can help you are:

- A competent Arboricultural Consultant

- An AA Registered Consultant

- Your Local Planning Authority

Trees near buildings and people

The proximity of trees to buildings can cause nuisance and inconvenience – for example through direct building damage, heavy shade or falling debris. Trees in adjacent property overhanging boundaries or blocking light are frequently a cause of annoyance or inconvenience, and there may be remedies available to alleviate this. For further advice contact a competent Arboricultural Consultant or a competent Arboricultural Contractor.

As a tree owner you have a legal duty of care to do what is reasonable to prevent harm being caused to others by your trees.

If located close to people or objects of value, the risks posed by the trees should be assessed by a competent Arboricultural Consultant. The frequency and level of this assessment will vary from location to location and tree to tree. On occasion, remedial work or tree removal might be required.

Building subsidence and heave

Occasionally trees can cause subsidence or heave damage to structures. If you notice cracks to your building, the first thing you should do is contact your building insurers who will investigate.

If agents for your neighbour’s house ask you to carry out work to your trees because of alleged damage the trees have caused, you should advise your own building insurers and if necessary instruct a competent Arboricultural Consultant and possibly a Structural Engineer to assess the situation.

Subsidence and heave require a multi-disciplinary approach, involving a range of professionals. The following professionals should be able to help you:

- A competent Arboricultural Consultant or AA Registered Consultant

- A competent Structural Engineer

- A competent Geotechnical Expert

- Your Buildings Insurance Company

Tree Selection, Planting and Maintenance

Selecting the right tree for the right place

Planting a tree in your garden is a decision requiring forethought and planning. Consideration must be given to the surrounding landscape and buildings, space available, soil type and location of the particular site.

Careful thought will help to ensure that an appropriate species is selected for the particular location, so giving the tree the best chance of successful establishment and future growth.

The Trees and Design Action Group (TDAG) offer comprehensive guidance with their resource Tree Species Selection for Green Infrastructure: A Guide for Specifiers, which includes information for over 280 species on their use-potential, size and crown characteristics, natural habitat, environmental tolerance, ornamental qualities, potential issues to be aware of, and notable varieties.

Further advice and information can be obtained from the Help & Advice section of this website as well as an AA Registered Consultant.

Tree planting

It is essential that young trees are given every opportunity to survive planting. Poor planting practices can result in long-term problems and even the death of the tree.

Information on how to plant your trees can be obtained from a competent Arboricultural Consultant, a competent Arboricultural Contractor, Specialist tree planting contractors or Tree nurseries.

Maintenance in the first few years following planting is crucial to ensure establishment. Young trees need TLC:

- Tending – check stakes, ties, guards and prune out broken and diseased branches

- Loosen ties and remove the stake altogether if the tree is stable

- Clear vegetation from around the base

- Add water when required

Tree maintenance

Most trees do not require regular pruning but there are occasions when tree work is necessary. You must take great care in deciding who you will take advice from.

Trees can suffer ill health from pests and diseases and or as a result of climatic or environmental changes.

If your tree looks unwell, appears different to normal or you consider that tree works might be required, you can obtain guidance and advice from the following sources:

- A competent Arboricultural Consultant

- A competent Arboricultural Contractor

- Download this leaflet – ‘Tree Work: Choosing your tree surgeon (arborist)’

- Download this leaflet – ‘Guide to Tree Pruning’

- Visit our Help & Advice section of this website

Guide to Tree Pruning

Tree Pruning is part of a series of general information leaflets produced by the Arboricultural Association.

The Association provides membership services, accreditation and support to 3,000 professional arborists in the UK and further afield.

We strongly recommend that you use an accredited ARB Approved Contractor or AA Registered Consultant who has been vetted and approved by the Arboricultural Association.

You can find an accredited tree surgeon or consultant though our directories at www.trees.org.uk/Find-a-professional Please note the association is not able to provide direct advice to the general public.

How a tree works

Before we discuss pruning, we need to consider what a tree is and how it works. An appreciation of the processes involved in the growth of tree will help us to understand the principles behind pruning.

A tree is a dynamic living organism that has a self-supporting woody stem. Through the process of photosynthesis the tree converts carbon from the atmosphere into sugars, which it uses to make the building blocks of cellulose and lignin required to sustain its self-supporting structure. The sugars produced are transported throughout the tree via the inner bark area, known as the phloem, to where they are required; sugars not immediately required are stored within the trunk, branches and rooting system.

The tree roots absorb water and other essential nutrients and minerals from the soil, which are then transported to the leaves via tubular vessels called xylem. The minerals, along with the sugars produced via photosynthesis, are used to produce the flower and subsequently fruit to advance the next generation of trees.

Why prune your tree?

There are many reasons why trees might need pruning. These reasons could include improving the structure of the tree, to remove dangerous or defective branches; the reduction of shading, the reduction of wind loading or to provide clearance between the tree and a structure – to name just a few. Care must be taken however, as removing too big a branch can lead to disease entering the tree via the wound/s left behind, or reduce the vitality of tree due to the excessive volume of leaf bearing material being removed.

Before any branch is removed the following questions should be asked:

What will be the result of removing this branch?

Will it leave a large wound?

Will it remove a large area of leaf bearing material?

Will it leave the tree open to an increased risk of disease?

If the questions above can be answered with a “No” then the removal of the branch can proceed. It is very important to realise however, that the removal of tree branches can be a dangerous process and the safest option, particularly if the branch cannot be reached from the ground, is to employ a suitable trained and insured arborist (also known as a tree surgeon). A list of Arboricultural Association ARB Approved Contractors is available on our web site at www.trees.org.uk/Find-a-professional

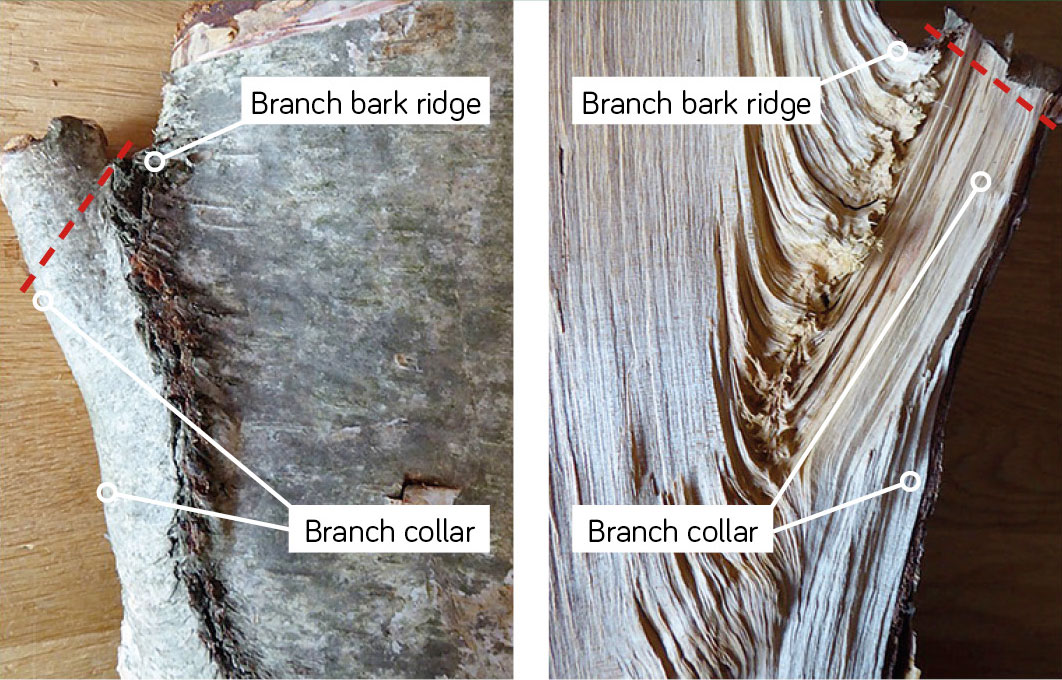

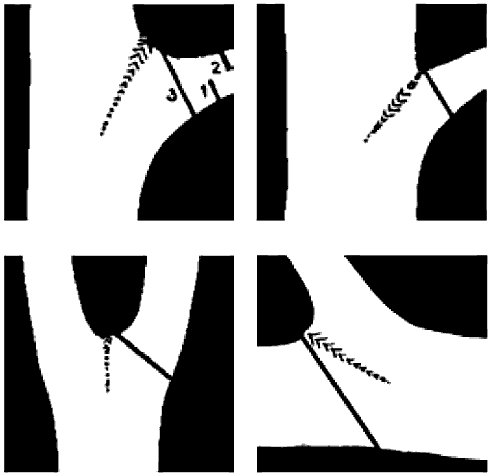

Figure 1 – Optimum position of the final pruning cut

How to prune a tree

Branches were once buds that became twigs, and over time and incremental growth, have gone on to form a branch. As the tree produces an annual ring of growth, so does the branch, strengthening the attachment of the branch to the tree. This attachment point will sometimes exhibit a strip of raised bark known as a ‘branch bark ridge’ on the top and sides of the branch and a ‘branch collar’, which is the area around the base of the branch.

To keep the wound as small as possible, the British Standard for tree work (BS 3998: 2010 Tree Work – Recommendations) states that the diameter of the final cut should not exceed one third of that of the parent branch or stem.

To remove the branch, a sequence of step cuts should be made with a shallow cut being made first on the underside leading to a top cut outside i.e. past, the underside cut. This will reduce the risk of the branch tearing down the stem and leaving an unsightly and potentially damaging wound; the final pruning cut can then be made at the branch bark ridge and branch collar.

When removing a branch, the final cut should be made from the branch bark ridge to the branch collar, along the red dotted line in figure 1. By following the imaginary red dotted line, the size of wound, in relation to the parent stem, will be left as small as possible. Some branches do not form a distinct branch collar, where this occurs, the cut should be made so as not to damage the branch bark ridge whilst leaving a small diameter wound.

If a large diameter branch is removed, the risk of disease entering the wound increases. Certain fungi and bacteria can enter the tree via these wounds and cause the woody structure of the tree to decay. Although decay is a normal process in terms of a trees life cycle, advancing this process by incorrect pruning can have serious consequences by compromising the health and structural integrity of the tree.

When to prune

If the decision has been made to prune or remove a branch, then a decision has to be made when to carry out the work. Pruning should generally occur after the leaves have ‘flushed’ and hardened, so late spring through summer. There are some exceptions, however, as some species such as Birch, Walnut and Maples, will ‘bleed’ sap and risk losing valuable sugars in the process if pruned in early spring, therefore the pruning of these trees should be carried out when this risk is low i.e. summer or mid winter.

Species belonging to the genus Prunus such as Cherry partially rely on the production of a resin or gum to aid in the defence against wound related pathogens, therefore pruning should occur in the summer. In general, pruning should avoid periods where the exposed wood will be left open to severe conditions such as drought, frost, and periods of fungal sporulation (autumn). Table 1 below gives the appropriate time to prune for a number of species commonly planted or found growing naturally within the United Kingdom and Northern Ireland and also indicates species specific tolerance to pruning. It should be noted that in most circumstances, unless there is a potentially hazardous structural defect that needs to be addressed, it is always best to prune trees as little as possible, as removing large amounts of wood and foliage reduces the ability of the tree to photosynthesise and can put the tree under significant stress.

Please note: Trees may be legally protected and unauthorised work can lead to prosecution. It is also your responsibility to ensure that protected wildlife is not harmed. Further advice can be found on our website at www.trees.org.uk/Help-and-Advice

| Species | Tolerance to hard pruning Good, Fair or Poor | Optimum time to prune | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Deciduous trees | |||

| Acacia | Fair | Spring (late) | Living wood most obvious, dead can be easily identified |

| Ailanthus | Fair | Spring (late) to summer | |

| Alder | Fair | Spring (late) to summer | |

| Apple | Good | Winter (mid) | Prune every year for fruit production |

| Ash | Fair | Spring (late) to summer | |

| Beech | Poor | Spring (late) to summer | |

| Birch | Poor | Summer or winter (mid) | Prone to bleeding |

| Cherry (& other Prunus sp. e.g. Almond, Apricot, Peach, Plum) and Silver leaf. Avoid fungal sporulation period (autumn) | Fair | Summer | Prone to drought, frost damage |

| Elm | Good | Spring (late) to summer | |

| Eucalyptus | Poor | Spring (late) to summer | |

| Hornbeam | Poor | Spring (late) to summer | |

| Horse Chestnut | Good | Spring (late) to summer | Avoid if possible as regrowth is weak and heartwood is quick to decay |

| Lime | Good | Spring (late) to summer | |

| Magnolia | Fair | Summer (mid) | Reduces bleeding and allows time for healing to begin |

| Maples (inc Sycamore) | Fair | Summer or winter (mid) | Prone to bleeding (Field maple less susceptible) |

| Mulberry | Good | Winter (mid) | |

| Oak | Good | Spring (late)to summer | |

| Plane | Good | Spring (late)to summer | |

| Poplar | Good | Winter (mid) | Prone to bleeding |

| Robinia | Good | Summer (mid to late) | Prone to bleeding |

| Rowan | Fair | Spring (late) to summer | |

| Walnut | Poor | Summer or winter (mid) | Prone to bleeding |

| Whitebeam | Poor | Spring (late) to summer | |

| Willow | Good | Spring (late) to summer | |

| Evergreen trees | |||

| Cedars | Poor | Winter (mid to late) | Avoid any pruning if possible. Shoots will not grow from old wood – therefore prune lightly. |

| Cypresses | Poor | Spring (late) to summer (early) | Shoots will not grow from old wood – therefore prune lightly |

| Firs | Poor | Summer (late) or winter (late) | Avoid any pruning if possible. Shoots will not grow from old wood – therefore prune lightly |

| Hemlock | Fair | Summer (late) or winter (late) | |

| Holly | Fair | Winter (mid to late) | |

| Holm oak | Poor | Winter (mid to late) | |

| Pines | Poor | Spring (late) | Avoid any pruning if possible as buds only at shoot tips. Newest growth can be removed during the spring |

| Spruce | Poor | Summer (late) or winter (late) | Shoots will not grow from old wood – therefore prune lightly |

| Western red cedar | Fair | Winter (mid to late) | |

| Yew | Fair | Summer (late) or winter (late) |

for Tree Owners, Managers, Contractors and Consultants

Ash Dieback Guidance

for tree owners

WHO is this guide intended for?

This guide provides practical advice and guidance for anyone who owns or manages ash trees, as well as tree contractors and consultants who may be employed to work on ash trees or provide site specific advice concerning their management. It directs people to where they can find more detailed information and relates to a wide range of sites where ash trees grow, including gardens, highways, open spaces, parks, woodlands and on development sites.

Liabilities can arise if trees and branches fall. This guide is not intended to substitute the site specific advice or guidance that can be provided by a suitably qualified and experienced tree contractor or consultant. The Arboricultural Association maintains a list of Registered Consultants and Approved Contractors who can offer advice and guidance to tree owners and managers and undertake tree pruning and felling work. Please contact the Arboricultural Association if you need help selecting an appropriate specialist. Details can be found at www.trees.org.uk

The evidence informing guidance for ash dieback is under constant review; this guidance will change accordingly to provide current advice. Please check the Help and Advice section of the Arboricultural Association website to obtain the latest version of this guide.

WHY the different names for the disease?

Ash dieback is caused by a fungus called Hymenoscyphus fraxineus (Hi-men-o-si-fus frax-in-e-us). Part of the fungus life cycle was formerly known as Chalara fraxinea, hence the alternative names including chalara or chalara ash dieback.

IMPORTANCE of ash in the UK

The common ash (Fraxinus excelsior) is one of our most important and prolific native tree species. The species accounts for 12% of broadleaved woodland in Great Britain and is commonly found in parks, gardens and hedgerows. They grow in a wide range of soils and climatic conditions, fulfilling roles in terms of amenity and ecosystem services, whilst providing valuable habitat for a wide range of species. There are 955 species associated with ash trees, of which 45 are believed to have only ever been found on ash.

IDENTIFYING the disease symptoms

Go to the guidance on the Forest Research website where you will find photographs and descriptive text to help identify the disease.

It is important to note that poor condition of the canopy might not be a result of ash dieback. Other problems such as drought stress, water logging, root damage, soil compaction, or other pests and diseases can cause ash trees to decline. Look out for basal lesions, honey fungus (Armillaria spp.), shaggy bracket (Inonotus hispidus) or giant ash bracket (Perenniporia fraxinea), all of which have potential to impair the structural integrity of ash trees.

For further technical information, and images, see

IMPACT of the disease

Thought to have originated in eastern Asia, ash dieback can be found in most parts of the UK. The disease is particularly destructive of our native, common ash. Trees are infected in the summer by airborne spores from fruit bodies occurring on the central stalks of fallen leaves – moist conditions favour the production of fruit bodies. Infection leads to dead branches throughout the crown. Not all ash trees will die as a direct result of ash dieback infection. A tree may be weakened so it becomes susceptible to other pests or diseases, and some trees will survive infection.

Whilst there is no evidence of full resistance to the disease, research and experience in Europe indicates that up to 5% of the ash population may be genetically tolerant to ash dieback. This natural tolerance in some trees provides an opportunity to maintain ash in the UK because the tolerance may be inherited.

The climate, site conditions and local tree cover appear to play a large role in the extent to which trees are affected by the disease. Local fragmentation of tree cover has been found to be an important factor with isolated trees, trees growing in open areas or trees in hedges far less affected than those in a forest environment. It has been shown that these trees will be subjected to a different microclimate with higher canopy temperatures, which are unfavourable to development of the disease. Host density has also been found to be important for disease development, with ash at a low density far less affected by ash dieback.

“The impact of the disease on trees outside of woodlands is less predictable. While many will decline, many will persist indefinitely.”

Forestry Commission/Defra – August 2019

Research suggests that whilst the possibility of 100% mortality in natural forests within 30 years can’t be ruled out, mortality between 50% and 75% may be more likely. In plantations 85% mortality is the highest recorded in Europe thus far.

Trees growing in well managed sites in open spaces such as parks show fewer symptoms.

“It is thought that trees are escaping the disease and at these sites, trees can survive for years without many observed symptoms.”

Defra – June 2019

It is thought that the same might apply to trees growing in streets and hedgerows.

Evidence shows that the disease will progress quickly in young and coppiced ash trees, trees suffering additional stresses, or when growing in ash dominated forests.

“Trees in forests are more likely to be more affected because of the greater prevalence of honey fungus and favourable microclimates for spore production and infection.”

Defra – June 2019

It is thought that the genetic and site related tolerance (field tolerance) of some trees might give rise to the continuation of ash in the landscape and that genetic tolerance might be the key factor in the restoration of ash as a forest tree.

Especially on humid sites, the fungus can cause [necrotic] lesions at the base of ash trees. These lesions, which are not always easy to spot, will often facilitate colonisation of the tree by secondary pathogens such as honey fungus (Armillaria spp.), making the trees structurally unstable. In some cases basal lesions have been observed on trees with few signs of crown dieback. Studies suggest that fewer basal lesions are present in hedges or isolated ash trees that are frequent on road sides and that their prevalence decreases the closer the trees grow to the road.

In addition to honey fungus (Armillaria spp.), there are other decay fungi associated with ash that should not be overlooked. Shaggy bracket (Inonotus hispidus) or giant ash bracket (Perenniporia fraxinea) may be observed, whether or not an ash tree is infected with ash dieback. Both of these decay fungi have potential to impair the structural integrity of ash trees.

As well as dieback of the crown, the pathogen causes premature leaf loss on affected trees and, as with any tree in poor health, both of these symptoms have the potential to inhibit wood production.

Research has shown that annual growth produced whilst a tree is affected by ash dieback is reduced in width, and exhibits reduced vessel diameter and fibre length (Tulik et al., 2018). The reduced growth will diminish the relative proportion of stronger, denser late wood and the more severe the infection, the more severe this impact is likely to be. Over a number of years the effect of this may be that the branch structure and potentially the trunk is mechanically weaker with increased risk of uncharacteristic breakages under loading, when felling, or when trees and branches hit the ground.

No evidence or research has come to light to suggest that wood made prior to being infected by ash dieback is weakened by the disease. However, where secondary pathogens are present they should not be overlooked.

For a full landscape epidemiology of ash dieback:

www.biorxiv.org/content/biorxiv/early/2019/03/22/582080.full.pdf

Tulik M, Yaman B, Kose N (2018) Comparative tree-ring anatomy of Fraxinus excelsior with Chalara dieback. Northeast Forestry University and Springer-Verlag GmbH Germany, part of Springer Nature 2018.

TAKING action to manage the impact

The tolerance of some ash trees, whether genetic or due to site conditions, should not be overlooked when taking action to manage the impact of ash dieback.

There are financial and practical implications relating to this disease that will need to be addressed. It is therefore vital that people and organisations responsible for managing ash trees and forests containing ash understand the implications and take timely, site specific and proportionate action to prepare for this.

If affected trees are situated in high footfall areas this can create health and safety risks, but it doesn’t necessarily follow that all ash trees growing in these areas will need to be removed or that they will all die. Uninfected ash trees should not be felled unless there are other overriding management requirements to do so and if all necessary permissions are in place.

“With the exceptions of felling for public safety or timber production, we advise a general presumption against felling living ash trees, whether infected or not.”

Forest Research

Monitoring should happen with increased frequency and at an appropriate time of year for assessing the extent of infection.

Considering the impact on amenity and biodiversity, resourcing the tree works and gaining political support are important considerations, but public safety is likely to be one of the biggest management issues for owners of ash trees. Trees in areas with high levels of public access need to be managed carefully for risks to public safety and appropriate action must be taken.

“Natural regeneration will encourage the process of natural selection for tolerance, so healthy trees should be maintained for as long as possible to ensure regeneration from tolerant mother trees.”

Defra – June 2019

Tree owners should, however, take a balanced and proportionate approach. Not all infected ash trees will need to be removed and pruning shouldn’t be ruled out as a management option, particularly where trees show a tolerance to the disease.

“Removal of leaf litter may be an effective way to reduce the level of inoculum in urban environments…”

Defra – June 2019

Clearing leaves may disrupt the fungus’s life cycle and slow the impact of ash dieback in urban areas.

Guidance on trees and public safety produced by the Forestry Commission can be found on the National Tree Safety Group website:

ntsgroup.org.uk/guidance-publications/

Ash dieback – infected canopy. ©Forestry Commission

TREE Preservation Orders and Conservation Areas

Ash trees may be protected by a tree preservation order, or a conservation area, or be the subject of a planning condition. Check first with the local planning authority and obtain any necessary written consent before proceeding with works to prune or fell protected ash trees.

Applications and notices seeking consent or advising of intent to prune or fell infected or uninfected ash trees should be judged on their merits, assessing the impact of the proposal on the amenity of the area and whether the proposal is justified.

The potential for a tree to become infected with ash dieback should not be a material consideration when determining applications and notices to prune or fell protected ash trees.

Evidence of tolerance or evidence of trees seemingly escaping the disease because, for example, they grow in open sites, should be taken into account. Biodiversity value as the ash population diminishes is another consideration.

Please note, in certain circumstances you may still need other permissions from other organisations before you can fell the tree(s), even if they are not protected by a Tree Preservation Order or growing in a Conservation Area.

TREES on Development Sites and Planning Conditions

As part of any tree survey intended to support a planning application, trees should be assessed and categorised using the criteria shown in Table 1 of British Standard 5837:2012 – Trees in relation to design, demolition and construction – Recommendations (BS5837). This will identify the quality and value of the existing trees, and inform decisions about retention or removal.

Current knowledge does not provide clarity on the impact of ash dieback on the life expectancy of individual ash trees, although up to 5% of ash trees will show genetic tolerance to the disease and many trees growing in open sites may not succumb to the disease and are likely to persist indefinitely. On these grounds it would be unreliable and premature to downgrade a healthy ash tree or one showing tolerance when categorising trees in accordance with BS5837 simply because of a presumption that life expectancy will be shortened.

The movement of ash planting stock is banned under a Plant Health Order. As a consequence, substitute species will be needed to fulfil extant landscaping conditions. If an ash tree planted before the ban dies, an alternative replacement species will be required.

Ash dieback – infected sapling. ©Forestry Commission

FELLING Licences

A felling licence granted by the Forestry Commission is required for the felling of growing trees, unless an exception as set out in the Forestry Act 1967, as amended, or the Forestry (Exceptions from Restriction of Felling) Regulations 1979 applies.

Everyone involved in the felling of trees must ensure that a felling licence has been issued before any felling is carried out, or that one of the exceptions applies.

If one or more of the exceptions within the legislation applies, there is no requirement to consult the Forestry Commission before doing the work. However, you should gather site specific evidence that shows a felling licence was not required before you start any felling. A Forestry Commission investigator may visit the site after the felling takes place and it is your responsibility to prove that an exception applies.

Guidance relating to felling licences, exceptions and how to apply for a licence can be found in the booklet ‘Tree felling – getting permission’.

Please note, in certain circumstances you may still need other permissions from other organisations before you can fell the tree(s), even if you do not need a felling licence.

For further guidance:

www.gov.uk/guidance/tree-felling-overview

www.gov.uk/guidance/tree-felling-licence-when-you-need-to-apply

To get the Tree Felling – Getting Permission PDF:

www.gov.uk/government/publications/tree-felling-getting-permission

REPLACING Ash Trees Removed Due To Ash Dieback

Replacement tree planting should take account of site constraints. It is important to diversify the species and to think about provenance when selecting trees in order to maximize the landscapes resilience to pests, diseases and climate change. Consider utilizing natural regeneration, in particular from ash showing tolerance to ash dieback where it is appropriate to do so.

Ash dieback – lesion on 4 year old ash. ©Forestry Commission

BIOSECURITY Measures

There is no cure for ash dieback, but good biosecurity practice should always be followed, whether working in woodlands, in parks or open spaces, or in residential gardens. By doing so, you will help reduce the risk of introducing and spreading tree pests and diseases.

There are no restrictions on the movement of ash timber, branches or leaves, but a plant health order made in 2012 prohibits all imports of ash seeds, plants and trees into GB, and all inland movements within GB of the same material. The 2012 plant health order can be found online.

For general advice on biosecurity measures go to:

- Arboricultural Association biosecurity guidance note, which can be found online.

- Forestry Commission guidance on preventing the spread of tree pests and diseases, which can be found online.

For the 2012 plant health order:

www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/2012/2707/contents/made

The Arboricultural Association biosecurity guidance:

FURTHER GUIDANCE on Ash Dieback

For further technical information and images visit:

Links to further guidance on Ash Dieback can be found on the Arboricultural Association website at:

www.trees.org.uk/Ash-Dieback-Guidance

ADVICE for Tree Contractors

Advising Customers

If affected trees are situated in high footfall areas this can create health and safety risks, but it doesn’t necessarily follow that all ash trees will need to be pruned or removed or that they will all die. Where circumstances allow, there is considerable merit in retaining ash trees, particularly where they show a genetic tolerance to the disease, which may be passed onto new generations of trees, or where they grow in open areas where they might escape the disease.

“With the exceptions of felling for public safety or timber production, we advise a general presumption against felling living ash trees, whether infected or not.”

Forest Research

As well as dieback of the crown, the pathogen causes premature leaf loss on affected trees and, as with any tree in poor health, both of these symptoms have the potential to inhibit wood production.

Research has shown that annual growth produced whilst a tree is affected by ash dieback is reduced in width, and exhibits reduced vessel diameter and fibre length (Tulik et al., 2018). The reduced growth will diminish the relative proportion of stronger, denser late wood and the more severe the infection, the more severe this impact is likely to be. Over a number of years the effect of this may be that the branch structure and potentially the trunk is mechanically weaker with increased risk of uncharacteristic breakages under loading, when felling, or when trees and branches hit the ground.

No evidence or research has come to light to suggest that wood made prior to being infected by ash dieback is weakened by the disease. However, where secondary pathogens are present they should not be overlooked.

Dead trees are prone to collapse or fall and dead branches are prone to break. Lesions might be present near the base of trees and honey fungus (Armillaria spp.) often associated with these lesions can weaken trees and make them more prone to falling. Where this is likely to pose a safety hazard, for example adjacent to a road, footpath or in a heavily used area, trees should be managed carefully, and where necessary be pruned or felled.

“With the exceptions of felling for public safety or timber production, we advise a general presumption against felling living ash trees, whether infected or not.”

Forest Research

Honey fungus (Armillaria spp.) is known to be associated with ash dieback, but it is important not to overlook other diseases associated with ash. For example, shaggy bracket (Inonotus hispidus) and giant ash bracket (Perenniporia fraxinea). Both diseases have potential to significantly impair the structural integrity of ash trees.

Clearing leaves may disrupt the fungus’s life cycle and slow the impact of ash dieback.

Where appropriate, you should advise clients with ash trees growing in open and urban areas to remove all ash leaf litter in the autumn/winter. The leaves should be burnt, buried or composted.

It is not necessary to fell or reduce uninfected ash trees as a precautionary measure. Uninfected ash trees should only be pruned or felled to meet other, unrelated management objectives.

Remember to check if the trees are protected by a tree preservation order or conservation area, or if a felling licence is needed.

If it is necessary to remove trees due to their condition and the circumstances in which they grow, advise customers of the importance to replace them and if possible, discuss the choice of species suited to the site.

Ash dieback – leaf symptoms. ©Forestry Commission

Planning Works and Managing The Risks

- Ensure you can identify ash trees, ash dieback, and other diseases associated with ash such as honey fungus, giant ash bracket and shaggy bracket correctly.

- Undertake a pre-condition assessment, examining the health and structural condition of the tree. Pay particular attention to the appearance of foliage at branch tips, the basal condition, the presence of deadwood, and discoloured or fractured unions within the canopy.

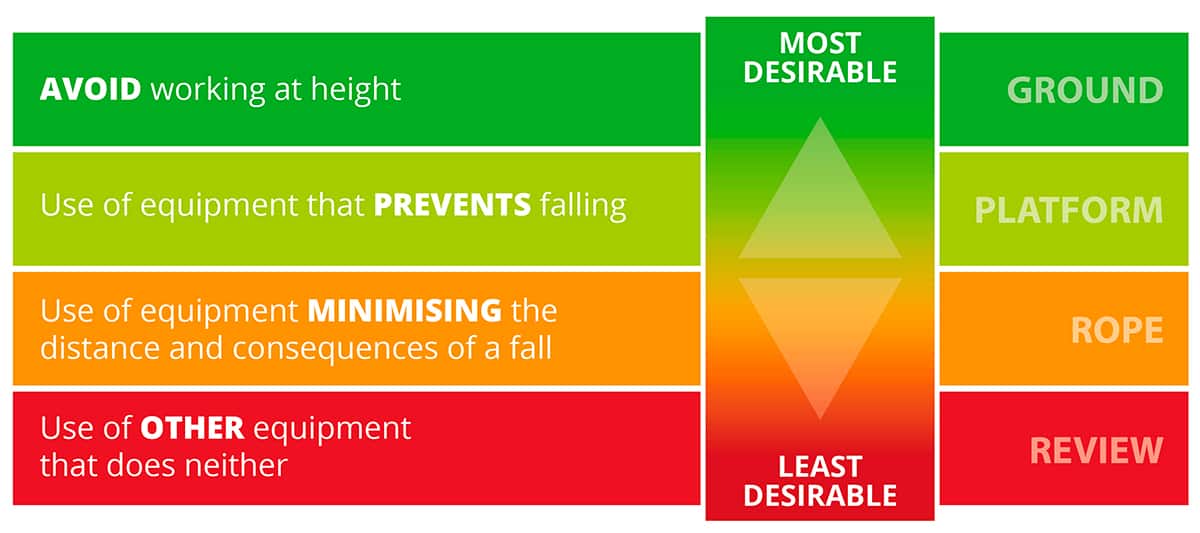

- When planning, resourcing and managing tree work have regard to the Industry Code of Practice ‘Tree Work at Height’, which can be found online. Adhere to the tree work at height risk hierarchy (see below) to ensure safe and effective tree work.

- All site personnel should contribute to job planning, raise points of concern and stop work if something is unclear or a safety issue arises.

- The selection of any load bearing anchor point should be carried out in accordance with current good practice. In particular, anchor points should be visually inspected, selected as capable of withstanding any foreseeable loading and loaded with a climber’s full body weight prior to committing to that anchor.

- During tree climbing operations, climbers must constantly assess the suitability of any anchor chosen and its intended use e.g. during branch walking where loading on an anchor is likely to be different to that of during access or descent. Situations were dynamic loading to an anchor may occur i.e. slack in a climbers system, working above an anchor, must be avoided, along with horizontal loading of an anchor, to avoid any potential bending moment.

- The use of dismantling techniques whereby the tree is to be used as the same anchor as the climber must only be undertaken following a robust risk assessment that has discounted safer ways of working. Where using ‘free-fall’ techniques, take account of the risks associated with debris breaking up as it hits the ground, and any extension to drop zones that may be required to account for this.

- Where practicable, use machinery such as a harvester or tree shear to fell trees. Where this isn’t possible use recognised tree felling techniques to maintain control of the tree during the felling operation considering the effects of a barber chair and brittle hinge fibres. Modify felling technique to account for this e.g. use of holding cuts, thicker hinge dimensions.

- The suitability of using felling aids such as wedges that may need to be driven into the back of a tree resulting in stem shake, or assisted felling techniques whereby a force may be applied to the stem prior to felling must be carefully considered in regard to brittle hinge fibres.

- Planning of tree felling operations must include provision for good escape routes so any loose or breaking branches can be avoided if they fall.

- Guidance on safety measures to undertake during felling can be found on the Forestry Industry Safety Accord (FISA) website. Read Safety Guidance for Managers – Felling Dead Ash which can be found online.

Tree work at height –– risk hierarchy

To download the Industry Code of Practice ‘Tree Work at Height’ please visit:

To download the Safety Guidance for Managers – Felling Dead Ash guidance please visit:

Further References:

Key ash dieback management guidance:

- Managing woodlands in light of ash dieback (FC Ops Note 046)

- Managing woodland SSSIs with ash dieback (NE+FC)

- The management of individual ash trees affected by ash dieback (FC Ops Note 046a)

Other ash dieback guidance and information that may be useful:

- Ash dieback introduction and signposting leaflet (FC+Defra)

- 10 case studies on Managing ash dieback (RFS+FC)

- Felling dead ash – Safety guidance (FISA+Euroforest)

- Ash dieback Manual (Forest Research, ~live)

- Restocking grant for woodland (Countyside Stewardship on GOV.UK)

- Guidance on replacement species to mitigate the loss of ash (FC Research Note)

- Ash dieback symptoms etc (Observatree, –live)

- Toolkit for Local Authorities etc (Tree Council)

- Map of infection spread across UK (FERA+DEFRA)

Other (non-ash specific) guidance and information that managers of ash should be aware of:

- Trees and public safety (National Tree Safety Group)

- Protected species information (good practice, habitat ID, licencing and penalties) (FC+NE on GOV.UK)

- Tree felling licence: when you need to apply (FC on GOV.UK)

- Tree Preservation Orders and trees in conservation areas (MHCLG on GOV.UK)

- Guidance and policy on woodland management (FC on GOV.UK)

- Information on tree pests and diseases (FC+APHA on GOV.UK)

- Guidance on preventing the spread of tree pests and diseases (FC+APHA on GOV.UK)

Acronyms:

- SSSI = Site of Special Scientific Interest

- FC = Forestry Commission

- NE = Natural England

- Defra = Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs

- RFS = Royal Forestry Society

- FISA = Forest Industry Safety Accord

- APHA = Animal and Plant Health Agency

- MHCLG = Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government

Do I need permission to carry out work on trees on my property?

If your trees are protected by a Tree Preservation Order, or you are within a Conservation Area, or the trees are protected by a condition attached to a planning permission, then you will need consent for the works.

Find out if your tree has a TPO

More detailed information on TPOs: www.gov.uk/guidance/tree-preservation-orders-and-trees-in-conservation-areas#Flowchart-1-Making-and-confirming-TPO

What should I do if tree roots cause cracks in my driveway - does it mean that my house will be damaged next?

Tree roots typically grow close to the surface, and it is not uncommon for them to develop on the underside of hard surfaces such as driveways, which can lead to cracks developing through physical pressure.

This damage is frequently superficial, and there is a range of options available which include: do nothing; repair the cracks; remove the existing surface and replace with a new one engineered to accommodate the roots; prune the roots or remove the tree (the latter two subject to Tree Preservation Order (TPO) consent or conservation area notification if relevant).

Tree roots can cause problems by blocking drains. They do not usually cause the initial damage to the drain and will only enter drains which are already damaged and leaking. Therefore, if drains are watertight, roots should not normally affect them. If your drains are blocked by roots you will need a drainage company to assist. It is possible that the drains will require lining or replacing. Removing the tree seldom resolves the problem as the drain remains damaged and can leak (possibly causing foundation damage) or may be infiltrated by the roots of other plants unless the drain is repaired.

If your driveway or drains have been affected by roots, this does not necessarily mean that your house will be damaged next. Root damage to buildings is much rarer and is usually caused by subsidence: an entirely different mechanism to driveways and drains damage.

Further information:

- Tree Roots in the Built Environment 2006 (DCLG)

- Building Research Establishment publications

- AA Registered Consultants

- More detailed information on TPOs: www.gov.uk/guidance/tree-preservation-orders-and-trees-in-conservation-areas#Flowchart-1-Making-and-confirming-TPO

A brief guide to tree work terminology and definitions

![]() 24/11/2015 Last Modified: 08/11/2018

24/11/2015 Last Modified: 08/11/2018

WHAT’S IN A WORD?

Tree pruning may be necessary to maintain a tree in a safe condition, to remove dead branches, to promote growth, to regulate size and shape or to improve the quality of flowers, fruit or timber. Improper pruning can lead to trees becoming unsightly, diseased and/or potentially dangerous.

It is important that clients understand the basic terms commonly used to describe tree work operations so that they can ask for what they want or understand what the arboriculturist is recommending. Did you know, for example, that a ‘crown thin’ will not reduce the height of the tree? Nor will a ‘crown lift to 4m’.

The three main pruning options are shown below, and after that a glossary of other terms that you may find helpful. These are very general summaries and the Arboricultural Association can provide more detailed guidance by leaflets and other publications.

The British Standards most relevant to arboricultural work are:

BS3998: 2010 Recommendations for Tree Work and

BS5837: 2012 Trees in Relation to Design, Demolition and Construction - Recommendations.

A word of caution: many trees are legally protected. Felling or even just pruning a protected tree without permission from your Local Planning Authority may be a criminal offence.

Always check for Tree Preservation Orders or Conservation Area restrictions with your local council’s Tree Officer and/or Planning Department before carrying out any works.

Main Pruning Definitions

Crown Thin

Crown thinning is the removal of a portion of smaller/tertiary branches, usually at the outer crown, to produce a uniform density of foliage around an evenly spaced branch structure. It is usually confined to broad-leaved species. Crown thinning does not alter the overall size or shape of the tree. Material should be removed systematically throughout the tree, should not exceed the stated percentage and not more than 30% overall. Common reasons for crown thinning are to allow more light to pass through the tree, reduce wind resistance, reduce weight (but this does not necessarily reduce leverage on the structure) and is rarely a once-only operation particularly on species that are known to produce large amounts of epicormic growth.

Crown Lift or Crown Raising

Crown lifting is the removal of the lowest branches and/or preparing of lower branches for future removal. Good practice dictates crown lifting should not normally include the removal of large branches growing directly from the trunk as this can cause large wounds which can become extensively decayed leading to further long term problems or more short term biomechanical instability. Crown lifting on older, mature trees should be avoided or restricted to secondary branches or shortening of primary branches rather than the whole removal wherever possible. Crown lifting is an effective method of increasing light transmission to areas closer to the tree or to enable access under the crown but should be restricted to less than 15% of the live crown height and leave the crown at least two thirds of the total height of the tree. Crown lifting should be specified with reference to a fixed point, e.g. ‘crown lift to give 5.5m clearance above ground level’.

Crown Reduction

The reduction in height and/or spread of the crown (the foliage bearing portions) of a tree. Crown reduction may be used to reduce mechanical stress on individual branches or the whole tree, make the tree more suited to its immediate environment or to reduce the effects of shading and light loss, etc. The final result should retain the main framework of the crown, and so a significant proportion of the leaf bearing structure, and leave a similar, although smaller outline, and not necessarily achieve symmetry for its own sake. Crown reduction cuts should be as small as possible and in general not exceed 100mm diameter unless there is an overriding need to do so. Reductions should be specified by actual measurements, where possible, and reflect the finished result, but may also refer to lengths of parts to be removed to aid clarity, e.g. ‘crown reduce in height by 2.0m and lateral spread by 1.0m, all round, to finished crown dimensions of 18m in height by 11m in spread (all measurements approximate.)’. Not all species are suitable for this treatment and crown reduction should not be confused with ‘topping’, an indiscriminate and harmful treatment.

Illustrations courtesy of European Arboricultural Council.

The importance of correct pruning cuts

Every pruning cut inflicts a wound on the tree. The ability of a tree to withstand a wound and maintain healthy growth is greatly affected by the pruning cut – its size, angle and position relative to the retained parts of the tree. As a general rule branches should be removed at their point of attachment or shortened to a lateral which is at least 1/3 of the diameter of the removed portion of the branch, and all cuts should be kept as small as possible. Examples of correct pruning cuts are shown as follows.

Showing sequence of removal to avoid damage to the retained parts

Diagram 2 – examples of correct pruning cuts. Drawings courtesy of European Arboricultural Council.

Other useful terms associated with tree work

Adaptive growth

An increase in wood production in localised areas in response to a decrease in wood strength or external loading to maintain an even distribution of forces across the structure.

Adventitious/epicormic growth

New growth arising from dormant or new buds directly from main branches/stems or trunks.

Bracing

Bracing is a term used to describe the installation of cables, ropes and/or belts to reduce the probability of failure of one or more parts of the tree structure due to weakened elements under excessive movement.

Branch bark ridge and collar

See diagram 3 section 3. Natural features of a fork or union that may or may not be visually obvious. Neither the branch bark ridge nor collar should be cut.

Callus

Undifferentiated tissue initiated as a result of wounding and which become specialised tissues of the repair over time.

Cavity

A void within the solid structure of the tree, normally associated with decay or deterioration of the woody tissues. May be dry or hold water, if the latter it should not be drained. Only soft decomposing tissue should be removed if necessary to assess the extent. No attempt should be made to cut or expose living tissue.

Co-dominant stems

Two or more, generally upright, stems of roughly equal size and vigour competing with each other for dominance. Where these arise from a common union the structural integrity of that union should be assessed.

Coppicing

The cutting down of a tree within 300mm (12in) of the ground at regular intervals, traditionally applied to certain species such as Hazel and Sweet Chestnut to provide stakes etc.

Crown

The foliage bearing section of the tree formed by its branches and not including any clear stem/trunk.

Deadwood

Non-living branches or stems due to natural ageing or external influences. Deadwood provides essential habitats and its management should aim to leave as much as possible, shortening or removing only those that pose a risk. Durability and retention of deadwood will vary by tree species.

Decline

When a tree exhibits signs of a lack of vitality such as reduced leaf size, colour or density.

Dieback

Tips of branches exhibit no signs of life due to age or external influences. Decline may progress, stabilise or reverse as the tree adapts to its new situation.

Dormant

The inactive condition of a tree, usually during the coldest months of the year when there is little or no growth and leaves of deciduous trees have been shed.

Drop Crotching

Shortening branches by pruning off the end back to a lateral branch which is at least 1/3 of the diameter of the removed branch.

Fertilising

The application of a substance, usually to the tree’s rooting area (and occasionally to the tree), to promote tree growth or reverse or reduce decline. This will only be effective if nutrient deficiency is confirmed. If decline is the result of other factors such as compaction, physical damage, toxins etc., the application of fertiliser will not make any difference.

Formative pruning

Minor pruning during the early years of a tree’s growth to establish the desired form and/or to correct defects or weaknesses that may affect structure in later life.

Fungi/Fruiting bodies

A member of the plant kingdom that may colonise living or dead tissues of a tree or form beneficial relationships with the roots. The fruiting body is the spore bearing, reproductive structure of that fungus. Removal of the fruiting body will not prevent further colonisation and will make diagnosis and prognosis harder to determine. Each colonisation must be considered in detail by a competent person to determine the long term implications of tree health and structure when considered alongside the tree species, site usage etc.

Lopping and Topping

Generally regarded as outdated terminology but still included as part of Planning legislation. Lopping refers to the removal of large side branches (the making of vertical cuts) and topping refers to the removal of large portions of the crown of the tree (the making of horizontal cuts, generally through the main stems). Often used to describe crude, heavy-handed or inappropriate pruning.

Painting or Sealing

Covering pruning cuts or other wounds with a paint, often bitumen based. Research has demonstrated that this is not beneficial and may in fact be harmful. On no account should timber treatments be used as these are definitely harmful to living cells.

Pollard

The initial removal of the top of a young tree at a prescribed height to encourage multistem branching from that point, traditionally for fodder, firewood or poles. Once started, it should be repeated on a cyclical basis always retaining the initial pollard point, or bolling as it becomes known.

Retrenchment pruning

A form of reduction intended to encourage development of lower shoots and emulate the natural process of tree aging.

Root pruning

The pruning back of roots (similar to the pruning back of branches). This has the ability to affect tree stability so it is advisable to seek professional advice prior to attempting root pruning.

Topping

See Lopping and Topping.

Vitality

The degree of physiological and biochemical processes (life functions) within an individual, group or population of trees.

Topics:

adaptive growth, bracing, callus, cavity, coppicing, crown, crown lifting, crown raising, crown reduction, crown thinning, deadwood, definitions, dieback, glossary, lopping, terminology, topping

Find a Professional

If you need advice or tree management services - always use an Arb Approved Contractor (Tree work) or a Registered Consultant (Arboricultural consultant).

Are there any times of year when tree works should not be undertaken?

Ideally, tree works should not be undertaken during the springtime period, when the 'sap is rising' to enable the leaves to flush (come out) and photosynthesis to begin, and during the autumn, when the tree is drawing nutrients back into itself from the leaves as they go brown.

If works are undertaken in the spring then the tree may become more vulnerable to pest and disease attack. If works are carried out in the autumn then the tree will not be able to get all the nutrients that it needs for the next spring and the tree may be put under unnecessary stress, increasing the likelihood of disease.

Outside these periods most trees can be pruned at any time of the year, with a few exceptions:

Cherry, Plum and related trees (Prunus species) should be pruned soon after flowering to reduce the risk of bacterial infection.

Maple, Birch, Beech and Walnut should be pruned in leaf or just after leaf fall and Magnolia in high summer to avoid ‘bleeding’ (exuding sap), which, although not considered damaging, can be unsightly.

If possible, pruning should be avoided when recovery may be impaired, for example during a period of physiological stress following previous tree work or construction-related damage or during seasonal weather extremes such as drought or extended heavy frost.

Topics:

bleeding, fruit trees, pruning, time of year

Find a Professional

If you need advice or tree management services - always use an Arb Approved Contractor (Tree work) or a Registered Consultant (Arboricultural consultant)