Acute Oak Decline – Oak

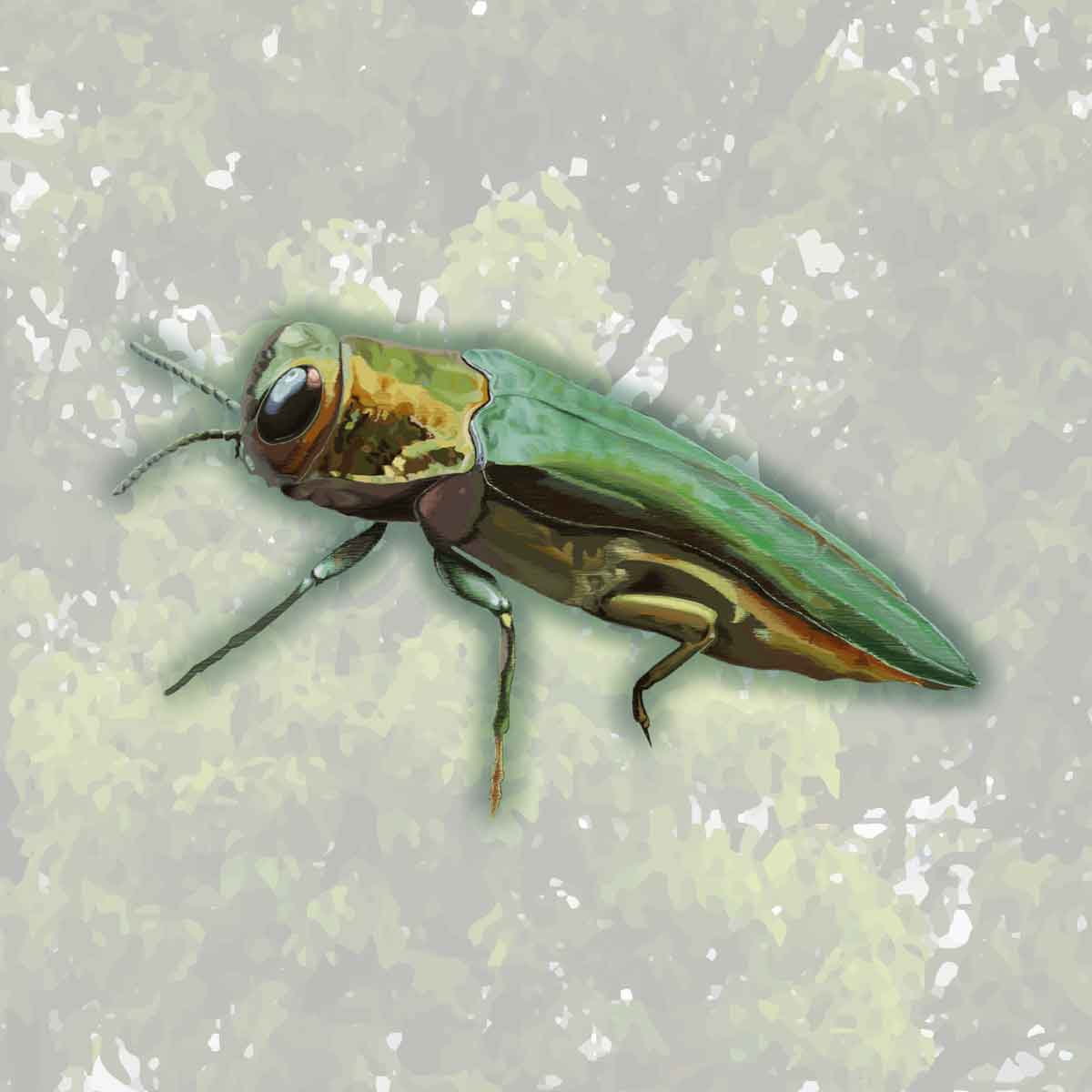

The Forestry Commission has also produced the following information about pests and diseases and associated biosecurity. Click a link below to find out more.

For more information on pests and diseases and how we can help reduce their spread, take a look at their website: www.gov.uk/guidance/prevent-the-introduction-and-spread-of-tree-pests-and-diseases

Information contained on this page are © copyright of the Forestry Commission and are used with their permission.

Preventing the introduction of harmful pests & diseases and the spread of exisiting issues

The Arboricultural Association works alongside many leading industry bodies to help promote best practice throughout both our membership but further afield too. To that end we have helped produce a Biosecurity Policy to help prevent spread on pests and diseases in our tree stock.

Biosecurity is the single most important subject in terms of safeguarding the future of our trees.

With the myriad of potential threats we aim to both give a clear best practice framework to those within the industry but also to help those with special interests around trees to be able to spot potential hazards and enable them to pass that information on to the relevant authorities.

Best practice guidance for Arborists working in any role in arboriculture and environmental sectors.

Equip yourself with the knowledge and tools to tackle biosecurity.

Guidance categorised by job roles from practical application to policy advisors.

Development near trees

Trees are easily damaged by construction works, regardless of their scale. Digging a garden pond may cause damage to trees in the same way as building demolition and construction.

It is important to ensure that trees are adequately assessed before ANY work takes place.

This is a complex topic. The specialists who can help you are:

The proximity of trees to buildings can cause nuisance and inconvenience – for example through direct building damage, heavy shade or falling debris. Trees in adjacent property overhanging boundaries or blocking light are frequently a cause of annoyance or inconvenience, and there may be remedies available to alleviate this. For further advice contact a competent Arboricultural Consultant or a competent Arboricultural Contractor.

As a tree owner you have a legal duty of care to do what is reasonable to prevent harm being caused to others by your trees.

If located close to people or objects of value, the risks posed by the trees should be assessed by a competent Arboricultural Consultant. The frequency and level of this assessment will vary from location to location and tree to tree. On occasion, remedial work or tree removal might be required.

Occasionally trees can cause subsidence or heave damage to structures. If you notice cracks to your building, the first thing you should do is contact your building insurers who will investigate.

If agents for your neighbour’s house ask you to carry out work to your trees because of alleged damage the trees have caused, you should advise your own building insurers and if necessary instruct a competent Arboricultural Consultant and possibly a Structural Engineer to assess the situation.

Subsidence and heave require a multi-disciplinary approach, involving a range of professionals. The following professionals should be able to help you:

Ash Dieback Guidance

for tree owners

This guide provides practical advice and guidance for anyone who owns or manages ash trees, as well as tree contractors and consultants who may be employed to work on ash trees or provide site specific advice concerning their management. It directs people to where they can find more detailed information and relates to a wide range of sites where ash trees grow, including gardens, highways, open spaces, parks, woodlands and on development sites.

Liabilities can arise if trees and branches fall. This guide is not intended to substitute the site specific advice or guidance that can be provided by a suitably qualified and experienced tree contractor or consultant. The Arboricultural Association maintains a list of Registered Consultants and Approved Contractors who can offer advice and guidance to tree owners and managers and undertake tree pruning and felling work. Please contact the Arboricultural Association if you need help selecting an appropriate specialist. Details can be found at www.trees.org.uk

The evidence informing guidance for ash dieback is under constant review; this guidance will change accordingly to provide current advice. Please check the Help and Advice section of the Arboricultural Association website to obtain the latest version of this guide.

Ash dieback is caused by a fungus called Hymenoscyphus fraxineus (Hi-men-o-si-fus frax-in-e-us). Part of the fungus life cycle was formerly known as Chalara fraxinea, hence the alternative names including chalara or chalara ash dieback.

The common ash (Fraxinus excelsior) is one of our most important and prolific native tree species. The species accounts for 12% of broadleaved woodland in Great Britain and is commonly found in parks, gardens and hedgerows. They grow in a wide range of soils and climatic conditions, fulfilling roles in terms of amenity and ecosystem services, whilst providing valuable habitat for a wide range of species. There are 955 species associated with ash trees, of which 45 are believed to have only ever been found on ash.

Go to the guidance on the Forest Research website where you will find photographs and descriptive text to help identify the disease.

It is important to note that poor condition of the canopy might not be a result of ash dieback. Other problems such as drought stress, water logging, root damage, soil compaction, or other pests and diseases can cause ash trees to decline. Look out for basal lesions, honey fungus (Armillaria spp.), shaggy bracket (Inonotus hispidus) or giant ash bracket (Perenniporia fraxinea), all of which have potential to impair the structural integrity of ash trees.

For further technical information, and images, see

Thought to have originated in eastern Asia, ash dieback can be found in most parts of the UK. The disease is particularly destructive of our native, common ash. Trees are infected in the summer by airborne spores from fruit bodies occurring on the central stalks of fallen leaves – moist conditions favour the production of fruit bodies. Infection leads to dead branches throughout the crown. Not all ash trees will die as a direct result of ash dieback infection. A tree may be weakened so it becomes susceptible to other pests or diseases, and some trees will survive infection.

Whilst there is no evidence of full resistance to the disease, research and experience in Europe indicates that up to 5% of the ash population may be genetically tolerant to ash dieback. This natural tolerance in some trees provides an opportunity to maintain ash in the UK because the tolerance may be inherited.

The climate, site conditions and local tree cover appear to play a large role in the extent to which trees are affected by the disease. Local fragmentation of tree cover has been found to be an important factor with isolated trees, trees growing in open areas or trees in hedges far less affected than those in a forest environment. It has been shown that these trees will be subjected to a different microclimate with higher canopy temperatures, which are unfavourable to development of the disease. Host density has also been found to be important for disease development, with ash at a low density far less affected by ash dieback.

Forestry Commission/Defra – August 2019

Research suggests that whilst the possibility of 100% mortality in natural forests within 30 years can’t be ruled out, mortality between 50% and 75% may be more likely. In plantations 85% mortality is the highest recorded in Europe thus far.

Trees growing in well managed sites in open spaces such as parks show fewer symptoms.

Defra – June 2019

It is thought that the same might apply to trees growing in streets and hedgerows.

Evidence shows that the disease will progress quickly in young and coppiced ash trees, trees suffering additional stresses, or when growing in ash dominated forests.

Defra – June 2019

It is thought that the genetic and site related tolerance (field tolerance) of some trees might give rise to the continuation of ash in the landscape and that genetic tolerance might be the key factor in the restoration of ash as a forest tree.

Especially on humid sites, the fungus can cause [necrotic] lesions at the base of ash trees. These lesions, which are not always easy to spot, will often facilitate colonisation of the tree by secondary pathogens such as honey fungus (Armillaria spp.), making the trees structurally unstable. In some cases basal lesions have been observed on trees with few signs of crown dieback. Studies suggest that fewer basal lesions are present in hedges or isolated ash trees that are frequent on road sides and that their prevalence decreases the closer the trees grow to the road.

In addition to honey fungus (Armillaria spp.), there are other decay fungi associated with ash that should not be overlooked. Shaggy bracket (Inonotus hispidus) or giant ash bracket (Perenniporia fraxinea) may be observed, whether or not an ash tree is infected with ash dieback. Both of these decay fungi have potential to impair the structural integrity of ash trees.

As well as dieback of the crown, the pathogen causes premature leaf loss on affected trees and, as with any tree in poor health, both of these symptoms have the potential to inhibit wood production.

Research has shown that annual growth produced whilst a tree is affected by ash dieback is reduced in width, and exhibits reduced vessel diameter and fibre length (Tulik et al., 2018). The reduced growth will diminish the relative proportion of stronger, denser late wood and the more severe the infection, the more severe this impact is likely to be. Over a number of years the effect of this may be that the branch structure and potentially the trunk is mechanically weaker with increased risk of uncharacteristic breakages under loading, when felling, or when trees and branches hit the ground.

No evidence or research has come to light to suggest that wood made prior to being infected by ash dieback is weakened by the disease. However, where secondary pathogens are present they should not be overlooked.

For a full landscape epidemiology of ash dieback:

www.biorxiv.org/content/biorxiv/early/2019/03/22/582080.full.pdf

Tulik M, Yaman B, Kose N (2018) Comparative tree-ring anatomy of Fraxinus excelsior with Chalara dieback. Northeast Forestry University and Springer-Verlag GmbH Germany, part of Springer Nature 2018.

The tolerance of some ash trees, whether genetic or due to site conditions, should not be overlooked when taking action to manage the impact of ash dieback.

There are financial and practical implications relating to this disease that will need to be addressed. It is therefore vital that people and organisations responsible for managing ash trees and forests containing ash understand the implications and take timely, site specific and proportionate action to prepare for this.

If affected trees are situated in high footfall areas this can create health and safety risks, but it doesn’t necessarily follow that all ash trees growing in these areas will need to be removed or that they will all die. Uninfected ash trees should not be felled unless there are other overriding management requirements to do so and if all necessary permissions are in place.

Forest Research

Monitoring should happen with increased frequency and at an appropriate time of year for assessing the extent of infection.

Considering the impact on amenity and biodiversity, resourcing the tree works and gaining political support are important considerations, but public safety is likely to be one of the biggest management issues for owners of ash trees. Trees in areas with high levels of public access need to be managed carefully for risks to public safety and appropriate action must be taken.

Defra – June 2019

Tree owners should, however, take a balanced and proportionate approach. Not all infected ash trees will need to be removed and pruning shouldn’t be ruled out as a management option, particularly where trees show a tolerance to the disease.

Defra – June 2019

Clearing leaves may disrupt the fungus’s life cycle and slow the impact of ash dieback in urban areas.

Guidance on trees and public safety produced by the Forestry Commission can be found on the National Tree Safety Group website:

ntsgroup.org.uk/guidance-publications/

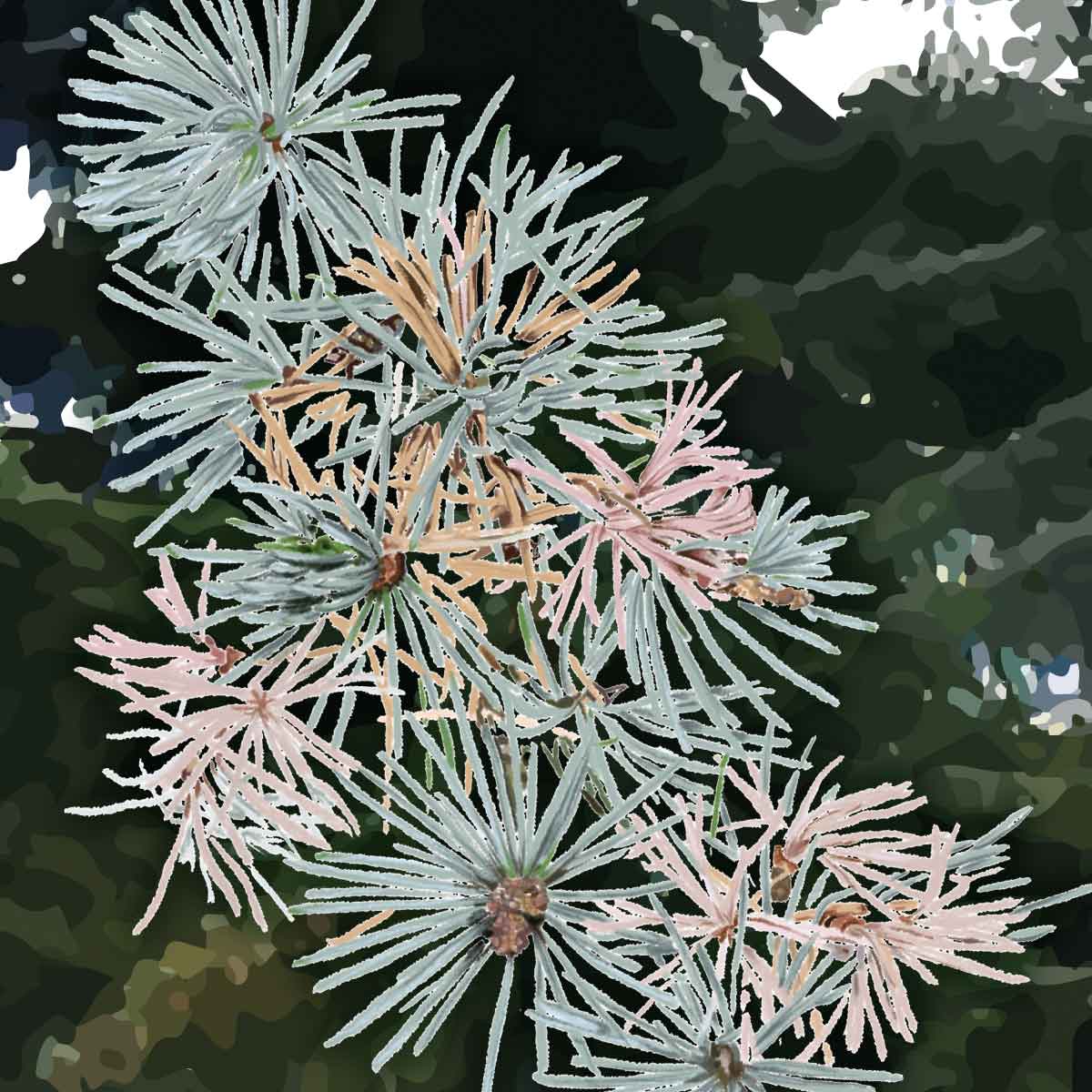

Ash dieback – infected canopy. ©Forestry Commission

Ash trees may be protected by a tree preservation order, or a conservation area, or be the subject of a planning condition. Check first with the local planning authority and obtain any necessary written consent before proceeding with works to prune or fell protected ash trees.

Applications and notices seeking consent or advising of intent to prune or fell infected or uninfected ash trees should be judged on their merits, assessing the impact of the proposal on the amenity of the area and whether the proposal is justified.

The potential for a tree to become infected with ash dieback should not be a material consideration when determining applications and notices to prune or fell protected ash trees.

Evidence of tolerance or evidence of trees seemingly escaping the disease because, for example, they grow in open sites, should be taken into account. Biodiversity value as the ash population diminishes is another consideration.

Please note, in certain circumstances you may still need other permissions from other organisations before you can fell the tree(s), even if they are not protected by a Tree Preservation Order or growing in a Conservation Area.

As part of any tree survey intended to support a planning application, trees should be assessed and categorised using the criteria shown in Table 1 of British Standard 5837:2012 – Trees in relation to design, demolition and construction – Recommendations (BS5837). This will identify the quality and value of the existing trees, and inform decisions about retention or removal.

Current knowledge does not provide clarity on the impact of ash dieback on the life expectancy of individual ash trees, although up to 5% of ash trees will show genetic tolerance to the disease and many trees growing in open sites may not succumb to the disease and are likely to persist indefinitely. On these grounds it would be unreliable and premature to downgrade a healthy ash tree or one showing tolerance when categorising trees in accordance with BS5837 simply because of a presumption that life expectancy will be shortened.

The movement of ash planting stock is banned under a Plant Health Order. As a consequence, substitute species will be needed to fulfil extant landscaping conditions. If an ash tree planted before the ban dies, an alternative replacement species will be required.

Ash dieback – infected sapling. ©Forestry Commission

A felling licence granted by the Forestry Commission is required for the felling of growing trees, unless an exception as set out in the Forestry Act 1967, as amended, or the Forestry (Exceptions from Restriction of Felling) Regulations 1979 applies.

Everyone involved in the felling of trees must ensure that a felling licence has been issued before any felling is carried out, or that one of the exceptions applies.

If one or more of the exceptions within the legislation applies, there is no requirement to consult the Forestry Commission before doing the work. However, you should gather site specific evidence that shows a felling licence was not required before you start any felling. A Forestry Commission investigator may visit the site after the felling takes place and it is your responsibility to prove that an exception applies.

Guidance relating to felling licences, exceptions and how to apply for a licence can be found in the booklet ‘Tree felling – getting permission’.

Please note, in certain circumstances you may still need other permissions from other organisations before you can fell the tree(s), even if you do not need a felling licence.

For further guidance:

www.gov.uk/guidance/tree-felling-overview

www.gov.uk/guidance/tree-felling-licence-when-you-need-to-apply

To get the Tree Felling – Getting Permission PDF:

www.gov.uk/government/publications/tree-felling-getting-permission

Replacement tree planting should take account of site constraints. It is important to diversify the species and to think about provenance when selecting trees in order to maximize the landscapes resilience to pests, diseases and climate change. Consider utilizing natural regeneration, in particular from ash showing tolerance to ash dieback where it is appropriate to do so.

Ash dieback – lesion on 4 year old ash. ©Forestry Commission

There is no cure for ash dieback, but good biosecurity practice should always be followed, whether working in woodlands, in parks or open spaces, or in residential gardens. By doing so, you will help reduce the risk of introducing and spreading tree pests and diseases.

There are no restrictions on the movement of ash timber, branches or leaves, but a plant health order made in 2012 prohibits all imports of ash seeds, plants and trees into GB, and all inland movements within GB of the same material. The 2012 plant health order can be found online.

For general advice on biosecurity measures go to:

For the 2012 plant health order:

www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/2012/2707/contents/made

The Arboricultural Association biosecurity guidance:

For further technical information and images visit:

Links to further guidance on Ash Dieback can be found on the Arboricultural Association website at:

www.trees.org.uk/Ash-Dieback-Guidance

If affected trees are situated in high footfall areas this can create health and safety risks, but it doesn’t necessarily follow that all ash trees will need to be pruned or removed or that they will all die. Where circumstances allow, there is considerable merit in retaining ash trees, particularly where they show a genetic tolerance to the disease, which may be passed onto new generations of trees, or where they grow in open areas where they might escape the disease.

Forest Research

As well as dieback of the crown, the pathogen causes premature leaf loss on affected trees and, as with any tree in poor health, both of these symptoms have the potential to inhibit wood production.

Research has shown that annual growth produced whilst a tree is affected by ash dieback is reduced in width, and exhibits reduced vessel diameter and fibre length (Tulik et al., 2018). The reduced growth will diminish the relative proportion of stronger, denser late wood and the more severe the infection, the more severe this impact is likely to be. Over a number of years the effect of this may be that the branch structure and potentially the trunk is mechanically weaker with increased risk of uncharacteristic breakages under loading, when felling, or when trees and branches hit the ground.

No evidence or research has come to light to suggest that wood made prior to being infected by ash dieback is weakened by the disease. However, where secondary pathogens are present they should not be overlooked.

Dead trees are prone to collapse or fall and dead branches are prone to break. Lesions might be present near the base of trees and honey fungus (Armillaria spp.) often associated with these lesions can weaken trees and make them more prone to falling. Where this is likely to pose a safety hazard, for example adjacent to a road, footpath or in a heavily used area, trees should be managed carefully, and where necessary be pruned or felled.

Forest Research

Honey fungus (Armillaria spp.) is known to be associated with ash dieback, but it is important not to overlook other diseases associated with ash. For example, shaggy bracket (Inonotus hispidus) and giant ash bracket (Perenniporia fraxinea). Both diseases have potential to significantly impair the structural integrity of ash trees.

Clearing leaves may disrupt the fungus’s life cycle and slow the impact of ash dieback.

Where appropriate, you should advise clients with ash trees growing in open and urban areas to remove all ash leaf litter in the autumn/winter. The leaves should be burnt, buried or composted.

It is not necessary to fell or reduce uninfected ash trees as a precautionary measure. Uninfected ash trees should only be pruned or felled to meet other, unrelated management objectives.

Remember to check if the trees are protected by a tree preservation order or conservation area, or if a felling licence is needed.

If it is necessary to remove trees due to their condition and the circumstances in which they grow, advise customers of the importance to replace them and if possible, discuss the choice of species suited to the site.

Ash dieback – leaf symptoms. ©Forestry Commission

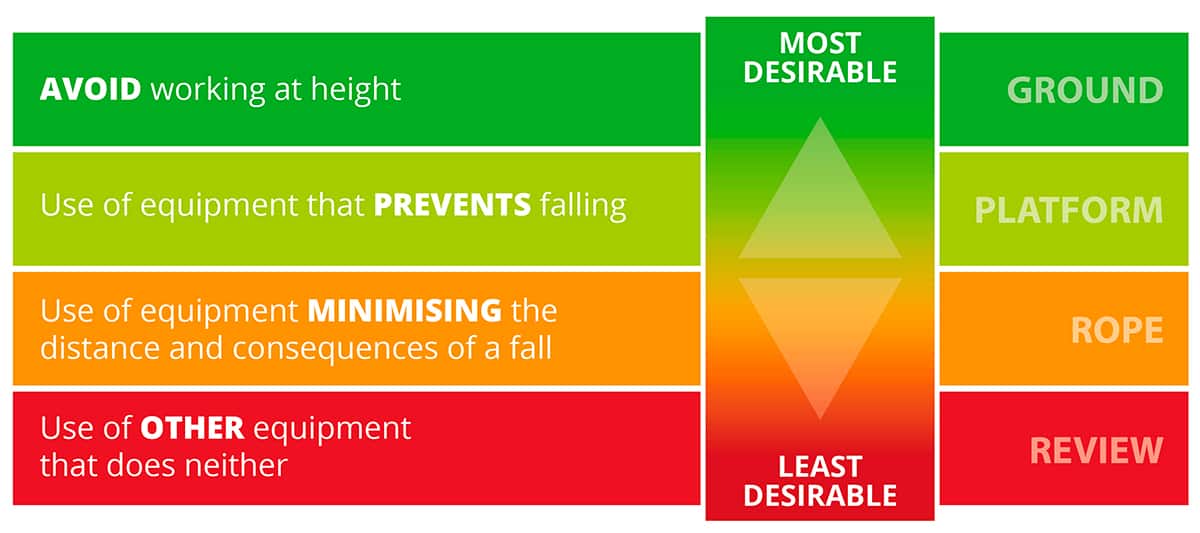

To download the Industry Code of Practice ‘Tree Work at Height’ please visit:

To download the Safety Guidance for Managers – Felling Dead Ash guidance please visit:

Will hammering a nail into a tree kill or harm the tree?

Hammering anything into a tree is intrusive and will cause harm; a tree is a living organism and an injury such as this is damaging.

The outer bark layer on a tree stem protects against disease and decay, anything that breaches it can allow the entry of harmful organisms.

The significance of any harm will depend on a number of factors such as the extent of the injury, the species and age of the tree and its overall condition.

For example, a single nail is unlikely to cause great harm to an established tree that has natural durability such as oak or sweet chestnut but it could be more harmful to a tree with lower durability such as birch or poplar.

What’s the fungus growing on my tree?

Will it kill the tree or make it unsafe?

If your tree is showing symptoms of ill health, which may be related to pest or disease, cultural or other reasons, you can send samples to the following organisations for analysis. Or consider engaging the service of an Arboricultural Association Registered Consultant or Approved Contractor. Please note: charges apply for these services.

The Forestry Commission and its tree health diagnostic and advisory service, Forest Research, offer analysis of and advice on tree health and related matters.

Tree Health Diagnostic and Advisory Service

Download the 'Report of tree problem for diagnosis' form

Analysis is also available from the Bartlett Tree Expert Research Laboratory

Books

Fungi on Trees - An Arborists' Field Guide

The most comprehensive photograph reference, detailing stages in development as well as close up studio shots as an aid to identification.

Apps

There are a number of online resources now available to help you identify fungi including several free fungi ID apps. The two below were both developed by arborists: